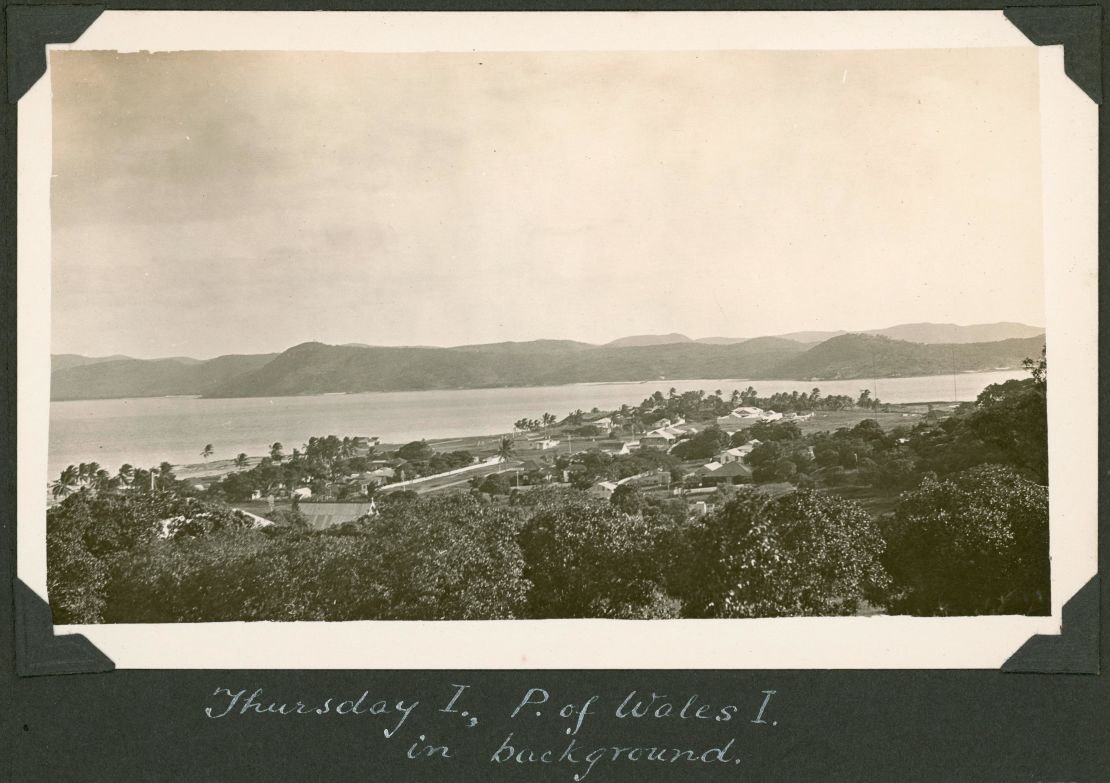

Milton Savage sits on the porch of his cement board house on Thursday Island in the Torres Strait, about 40 kilometers (24 miles) north of Australia’s northern tip.

Shaded by a lush tropical garden, Savage is stripped to the waist in a pair of footy shorts. He sips green tea and puffs on a cigarette while two old dogs lie on his feet wheezing in the monsoonal heat.

Savage is the Chair of the Kaurareg Native Title Aboriginal Corporation, the government-backed organization that lobbies for his people’s land rights, but he also has tribal bloodlines that tie him to all the clans of Cape York, in northern Queensland.

“I’m Kaurareg, I’m Italaig, Gudang Yadhaikana, Gomukudin, Kawaig man, that’s my people’s tribes,” Savage says, as steam rises from the nearby papaya and banana trees between monsoonal downpours.

Savage’s ancestors,the Kaurareg people, were well-established on the islands of the Torres Strait prior to European settlement but were nearly wiped out in a series of massacres that started in 1869. By the time they were marched off their traditional lands at gunpoint in 1922, only 80 people were left, including Savage’s maternal grandparents.

The massacres were part of Australia’s Frontier Wars, a series of bloody confrontations between European settlers and the country’s Indigenous population, that started soon after the First Fleet arrived in Botany Bay, south of Sydney, in 1788 and continued for almost 150 years.

“The Kaurareg are simply one of many displaced Indigenous groups in Australia,” said Professor Lyndall Ryan from the University of Newcastle, who has spent decades compiling stories handed down through generations. “The great tragedy is that Milton’s story is replicated across Australia.”

Saturday in Australia is National Sorry Day, the 20th time the annual event has been held, recognizing the mistreatment of the country’s Indigenous Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and remembering members of the Stolen Generations, the Indigenous children forcibly taken from their families under a government policy of assimilation.

Despite the promises of successive governments, little progress has been made in improving the quality of life for Australia’s Indigenous people, who make up 2.4% of the country’s population of 24 million people.

The Dreamtime

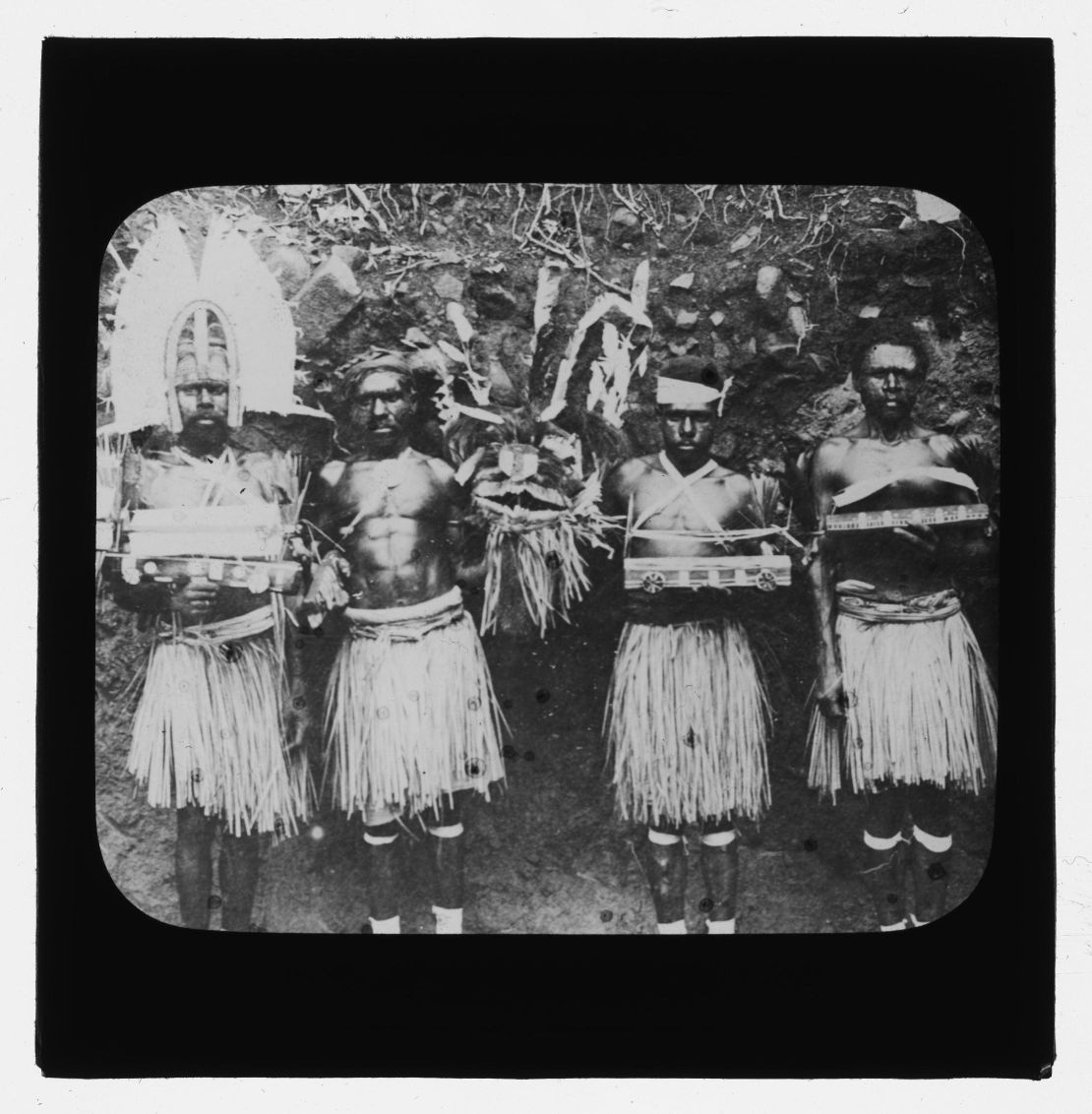

For thousands of years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders occupied land in the territory that is now called Australia, and among their people were 500 different clan groups or “nations,” many with distinctive cultures, beliefs and languages.

Their cultures are passed down through the generations in songlines, which map the land, sea and sky with traditional songs, stories, dance, and painting, in a belief system known as the Dreamtime.

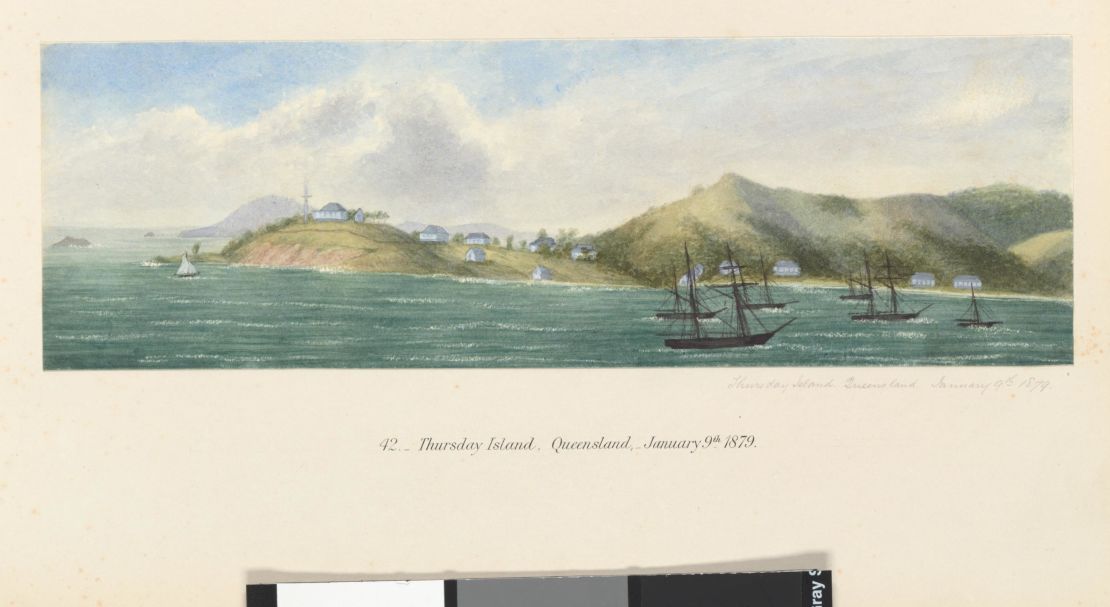

Thursday Island’s traditional owners call the island “Waibene.” It’s part of the Kaurageg Archipelago of 45 islands and islets known as Kaiwalagal.

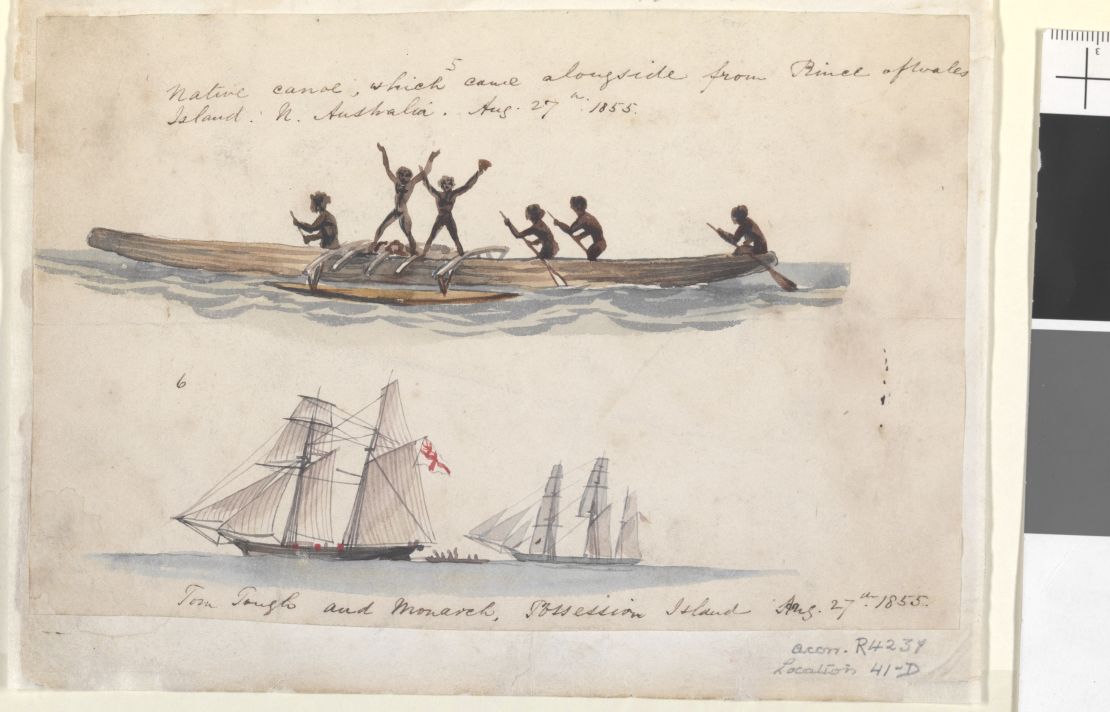

According to Kaiwalagal’s Dreamtime story, a giant mythical warrior, Waubin from Australia’s Central Desert, came to the island of Muralag (Prince of Wales Island) in the Torres Strait, where he dispersed other mythological warriors including Badhanai, a warrior of very small stature.

In a battle Badhanai darted underneath Waubin, slicing off his right leg with a bamboo knife. The blood from the wound flowed into Rabau Nguki, a waterhole whose creek carried it to the sea, where currents spread it throughout the waters surrounding the Prince of Wales group of islands.

As far as the blood spread became the territorial boundary of the Kaurareg.

It included the islands of Muralag (Prince of Wales), Bedanug (Possession) Narupai (Horn), Kiriri (Hammond), Kudalagal (Tuesday), Maururra (Wednesday), Waiben (Thursday) and Gealug (Friday), as well as others.

After the fight Waubin sat down in the ocean north-east of Kiriri, turned to stone (known now as the small island of Hammond Rock) and today protects the cluster sending strong currents around Muralag.

How the fighting started

Nonie Sharp, an anthropologist and LaTrobe University Research Fellow, has long documented the plight of the Kaurareg in several books on the subject.

“The Kaurareg were the closest geographically and socially and culturally to mainland Australia Aboriginal groups, and the white powers of the day regarded them as the ‘most backward’,” she said.

In 1864, the government established a new port called Somerset on the east of the Cape of York, putting British Royal Navy Marines in close proximity to the Kaurareg people.

Five years after they arrived, there was a massacre of Europeans which was described at the time as “undoubtedly one of the most frightful ever heard.”

Eight crew members of the small cutter Sperwer were killed and their bodies “put up into trees,” on Muralag or the Prince of Wales Island, according to police magistrate Frank Jardine, in a report published in The Queenslander newspaper in November 1869.

“As the heads and all the clothing have been taken off, they cannot be recognised,” wrote Jardine, who was an Australian explorer credited with daring exploits into northern Queensland where no white man had ever been.

The Kaurageg people were blamed for the Sperwer massacre and so began a series of retaliatory attacks, some of which were conducted by Jardine, which nearly wiped out the entire tribe, Savage said.

The attack was later found to have been carried out by a tribe of Islanders further to the East from the Island of Nagir.

Sharp has spent 30 years visiting the region collecting first person accounts from Kaurareg Elders, including Milton Savage’s grandparents, in the region and collating what scant records she could find, piecing together what happened to them.

“They were the forgotten people. There was very little record of what actually happened on the records to them other than what the missionaries the Anglican Church had,” Sharp said.

Savage said the oral history passed down through generations told of how the police ambushed them in the middle of the night, “while everyone was asleep and opened fire on everyone in the village.”

“They shot every man, women and child. For us here, we’re the ones that survived from our ancestors camping out around the island. That was the main population of my people.”’

Savage said the reverence shown to Jardine by modern-day Australia is at odds with the story passed down by his ancestors.

“Jardine, in the colonization history, he was a good man. But for us Indigenous people he was a murderer, he was a wicked man, and he died a very sinful death which was witnessed by everybody, a story that has been passed down from generation to generation.”

Jardine died of leprosy in 1919 and was revered in the local press at the time for his pioneering spirit and generous hospitality, paid partly by a haul of Spanish coins he found off the coast.

The story passed down through generations of Indigenous people is far different.

“We heard stories of (Jardine) riding on horseback, snatching babies from the mother’s arm and bashing the head against a tree, but yet they name streets, rivers and hotels after him, that is an insult,” Savage said.

The Jardine River in North Queensland carries his name, along with the surrounding National Park, Jardine Rock, Jardine Islet and Jardine Creek, among others.

“I really think the early settlers, their names, their stories they histories should be kept in a museum somewhere, not in the public places,” Savage said.

“The naming of the roads or buildings should come back to Traditional Owners, because this is our country, and the Australian people need to respect that.”

“But what is truth, what is true?” he added.

Families wiped out

Before European colonization, the population of First Nations people was estimated to be around 800,000 to one million. Within 100 years, their numbers were thought to have dropped to just 100,000, according to respected online Indigenous cultural resource Creative Spirits.

The sharp decline in population wasn’t just due to violent deaths, but also diseases brought by the Europeans, including the common cold, flu, measles, venereal diseases, tuberculosis and smallpox.

Downplaying of the bloodiest parts of Australia’s frontier wars history has become the battlefield of the ‘Culture Wars’, or ‘History Wars’ over the last two decades, where historians and politicians have argued over whether the country was invaded or colonized.

“We’ve got to acknowledge it, we have to heal, and we’re not going to heal until we acknowledge all of this,” Ryan, from the University of Newcastle, said.

Ryan is building an interactive map that shows where massacres have occurred across the country. Five years after she started, it’s still work in progress which she hopes to finish by the end of 2020.

“It’s going to be piecemeal and it’s going to be a long struggle, but my job is try and present the evidence of as many massacres as possible so that people can’t say it couldn’t have happened or it’s got nothing to do with us.

“When they realize how widespread and how pervasive it was and how horrible they were, I think then people will start changing a bit. But we have a long road in front of us.”

Ryan said many of the Queensland massacres, including the one on Muralag or Prince of Wales Island have yet to be included, and that many people, including her academic peers, have been shocked by the extent of the killings. “People just have no idea,” she said.

The historian thinks there is a reluctance by the Australia government to face the past. However, she thinks the national consensus is starting to shift.

“In the past I don’t think people wanted to know, it was too hard. So what I’m trying to do is go, ‘here’s the evidence I’ve found, here’s the number of massacres that I can stand up in court and defend.’ That’s when people have to say, ‘OK I accept that.’”

“It’s taken a long time to get this far, we should have known this a hundred years ago.”

For Savage, recognition is long overdue.

“People tell us we should just get over it, get over the past, but we need to understand these things, why they happened,” he said.

“We can’t change the past but we can learn from the past and make sure nobody makes the same mistakes ever again.”