They came to help rebuild Britain after the devastation of World War Two, invited by the UK government to lay roads, drive buses, clean hospitals and nurse the sick.

Known as the Windrush generation – the first of their numbers came on the Empire Windrush passenger liner in June 1948 – they were the first large group of Caribbean migrants to arrive in the UK. They came to symbolize the seismic demographic changes that took place in post-war Britain, when hundreds of thousands of people came to the United Kingdom from former British colonies, known as the Commonwealth.

But in recent years, successive British governments have sought to appear tough on illegal immigration, and their descendants are now struggling to prove a citizenship status they previously took for granted. In essence, the children of the Windrush generation are being told they might not be British after all.

Yet the Windrush generation are not illegal immigrants. Until a new immigration law came into force in 1973, Commonwealth citizens and their children had the automatic right to live and work in the UK. Many did so, without any need for additional documentation.

In recent years, however, changes to UK immigration law have caused significant problems for many of them.

‘Hostile environment’

Regulations introduced by Prime Minister Theresa May, when she was Home Secretary in the previous Conservative government led by David Cameron, require employers, landlords and health service providers to demand evidence of legal immigration status. In 2012, May described the measures as designed to create a “hostile environment” for people who were in the UK illegally.

The trouble is, many of the Windrush children don’t have the required documentation. As a consequence, some lost their jobs, others were evicted from their homes, and a few were reported to have been threatened with deportation.

The bubbling controversy exploded into a full-blown scandal at the weekend. For the first time in 20 years, the UK is hosting the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, a biennial summit of leaders of Commonwealth nations. A delegation of Commonwealth leaders requested a meeting with the Prime Minister to discuss the Windrush issue, which Downing Street – to widespread consternation – declined.

Stung by a wave of negative publicity, the government backed down and said a meeting would take place. Forced to appear before MPs in the House of Commons, Home Secretary Amber Rudd apologized for the “appalling” treatment of some of the Windrush migrants and promised that none of them would be deported for lack of documentation.

But many have gone through months of agony.

Glenda Caesar was just six months old in 1961 when she traveled from Dominica to the UK with her parents. After working for 16 years as an administrator with the National Health Service, she suddenly lost her job as she could not provide the necessary documentation.

“I worked as an administrator for the NHS and was told I have to leave as I did not have UK status,” she told CNN. “I am not working at present and still need documentation on my father and school or medical records as the final part.”

Labour MP David Lammy said in a tweet Monday that what was happening was “grotesque, immoral and inhumane,” and has rallied around 140 fellow MPs from all parties to call on the Prime Minister to immediately address the issue in parliament.

Guy Hewitt, the Barbados High Commissioner to Britain, said the scandal had affected many people. “They find themselves abandoned and made destitute by a country they have given their lives to,” he told Sky News on Monday.

Patrick Vernon, an expert on Caribbean family history in the UK, organized a petition that received more than the 100,000 signatures required for a debate on the issue to be held in parliament.

“It’s like telling the descendants of fourth generation Irish immigrants to the US that suddenly you might not be American after all and could be deported,” Vernon told CNN.

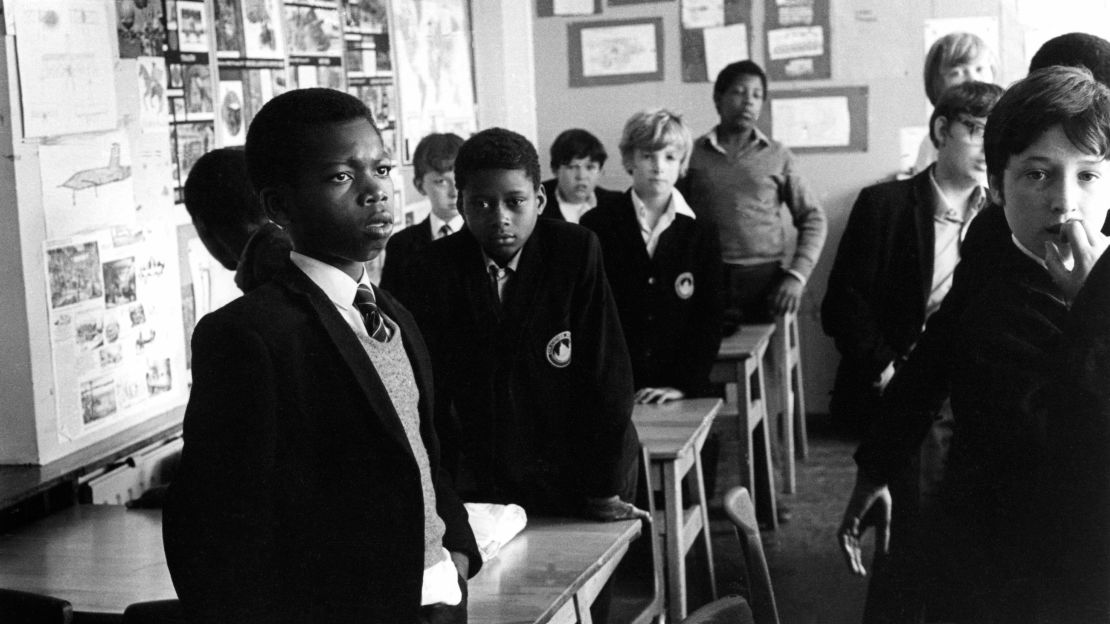

Vernon said he knew of people desperately trying to find photos of themselves in school playgrounds to prove how long they had been in the UK.

Conservative MP and Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government, Sajid Javid, said he was “deeply concerned” to hear about the difficulties some from the Windrush generation are facing, in a tweet on Monday.

“This should not happen to people who have been longstanding pillars of our community,” Javid said, adding that the government is looking into this matter “urgently.”

Satbir Singh, Chief Executive of the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants told CNN, called on the government to ease the process for members of the Windrush generation who sought to regularize their immigration status. “The government needs to make a clear guarantee that people seeking clarification of their status should have their rights guaranteed while they are doing so,” he said.

Singh said many of the people caught out are low-income earners who have not required a passport. And although it has been people from the Caribbean who have entered the media spotlight, there are also other people from former colonies in South Asia and Africa who might be affected,

By switching the onus on checking documents to the private sector, such as landlords and healthcare providers, he said the system has become “blatantly racist.”

“I’m second generation Indian and no matter how British my English is, I will always look like an immigrant,” he said.