Story highlights

Every 66 seconds, a new case of Alzheimer's disease is diagnosed

More than 5 million Americans live with the disease

It’s one of the holy grails of science: a cure for Alzheimer’s. Currently, there is no treatment to stop the disease, let alone slow its progression. And billionaire Bill Gates thinks he will change that.

“I believe there is a solution,” he told me without hesitation.

“Any type of treatment would be a huge advance from where we are today,” he said, but “the long-term goal has got to be cure.”

I had the chance to sit down with Gates recently to talk about his newest initiative. He sat in front of our cameras exclusively to tell me how he hopes to find a cure to a disease that now steals the memories and other cognitive functions of 47 million people around the world.

For Gates, the fight is personal. He is investing $50 million of his own money into the Dementia Discovery Fund, a private-public research partnership focused on some of the more novel ideas about what drives the brain disease, such as looking at a brain cell’s immune system. It’s the first time Gates has made a commitment to a noncommunicable disease. The work done through his foundation has focused primarily on infectious diseases such as HIV, malaria and polio.

I have interviewed Gates many times over the years, in countries around the world. He was more engaged on this topic of Alzheimer’s than I’ve ever seen before.

Today, Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia and the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, where a new case is diagnosed every 66 seconds. More than 5 million Americans live with the disease, at a cost of $259 billion a year. Without any treatment, those numbers are projected to explode to 16 million Americans with the disease, at a cost of over $1 trillion a year, by 2050.

“The growing burden is pretty unbelievable,” the tech guru-turned-philanthropist told me. It’s something he knows personally. “Several of the men in my family have this disease. And so, you know, I’ve seen how tough it is. That’s not my sole motivation, but it certainly drew me in.”

When he said, “I’m a huge believer in that science and innovation are going to solve most of the tough problems over time,” I could feel his optimism.

He told me he has spent the past year investigating and talking to scientists, trying to determine how best to help move the needle toward treatment of the disease itself rather than just the symptoms.

A disease turns 100

It has been more than a century since the disease was identified by German physician Dr. Alois Alzheimer. He first wrote about it in 1906, describing the case of a woman named “Auguste D.” Alzheimer called it “a peculiar disease,” marked by significant memory loss, severe paranoia and other psychological changes.

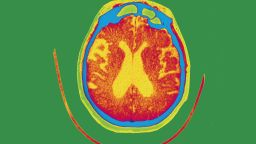

But it wasn’t until Alzheimer performed an autopsy on her brain that the case became even more striking. He found that her brain had shrunk significantly, and there were unusual deposits in and around the nerve cells.

It would take another 80 years for scientists to identify what those deposits were: plaques and tangles of proteins called amyloid and tau. They have become hallmarks of the disease.

Both amyloid and tau are naturally occurring proteins that can be found in healthy brain cells. But in a brain with Alzheimer’s, something goes haywire, causing parts of amyloid proteins to clump together and block the cell’s messaging pathways. Eventually, tau proteins begin to tangle up inside the neurons.

All of this contributes to a breakdown of the neural highway that helps our brain cells communicate. These changes in the brain can begin years before anyone starts actually exhibiting any symptoms of memory loss or personality changes.

Until recently, it’s been a challenge to understand the disease, let alone identify who has it. The only way to definitively diagnose Alzheimer’s is still after someone has died and their brain can be examined under the microscope, looking for the telltale amyloid plaques and tau tangles.

A new hope

“It’s gone slower than we all would have hoped. A lot of failed drug trials,” Gates told me. And he’s right. Since 2002, there have been more than 400 Alzheimer drug trials run and yet no treatments. There are some drugs prescribed to help with cognitive symptoms such as memory loss or confusion but nothing that actually targets Alzheimer’s.

In the past five years, advanced imaging technology has allowed us to see tau and amyloid in living people.

Dr. James Hendrix, who heads up the Alzheimer Association’s Global Science Innovation team, believes that this development is a game-changer. “You need good tools to find the right therapeutics,” he said.

By identifying these biomarkers earlier, Hendrix told me, scientists can work on finding ways to prevent the brain from deteriorating.

“If we can catch the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s, then we’re treating a mostly healthy brain, and keeping it mostly healthy. … It’s very difficult to repair the damage once it’s done,” he explained.

Dr. Rudy Tanzi agrees that imaging has been essential in understanding the pathology of Alzheimer’s and potential treatments. Tanzi, a professor of neurology at Harvard, has been at the helm of Alzheimer’s research, discovering several of the genes associated with the disease.

He points out that one of the greatest faults with some of the trials has not been in the treatment itself but in the application: too late in the disease’s progression, when symptoms are already occurring. “It’s like trying to give someone Lipitor when they have a heart attack,” he explained. “You had to do it earlier.”

Tanzi said we need to think about Alzheimer’s like cancer or heart disease. “That’s how we’re going to beat the disease: early detection and early intervention.”

Think different

Most of the focus in Alzheimer’s research has been on tau and amyloid, what Gates likes to call “the mainstream.” With his donation, Gates hopes to spur research into more novel ideas about the disease, like investigating the role of the glial cells that activate the immune system of the brain or how the energy lifespan of a cell may contribute to the disease.

“There’s a sense that this decade will be the one that we make a lot of progress,” Gates told me.

Gates believes that it will be a combination of mainstream and out-of-the-box thinking that will lead to potential treatments in the near future.

“Ideally, some of these mainstream drugs that report out in the next two or three years will start us down the path of reducing the problem. But I do think these newer approaches will eventually be part of that drug regimen that people take,” he said.

Join the conversation

Has looking into Alzheimer’s research caused Gates to worry about his own health?

“Anything where my mind would deteriorate” is, he said, one of his greatest fears. He’s seen the hardship it has caused in his own family. “I hope I can live a long time without those limitations.”

So Gates is now focused on prevention, by exercising and staying mentally engaged. “My job’s perfect, because I’m always trying to learn new things and meeting with people who are explaining things to me. You know, I have the most fun job in the world,” he said with a smile.

CNN’s Nadia Kounang and Roni Selig contributed to this report.