Editor’s Note: Fadi Hakura is a Turkey expert and associate fellow at Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, an independent policy institute based in London. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.

Over the past few months, relations between Turkey and Germany have become increasingly fraught.

Angela Merkel, the normally cautious German Chancellor, is reportedly considering placing potentially devastating economic pressure on Turkey in the hope that she can cool down Turkey’s increasingly confrontational President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Earlier this week, Sigmar Gabriel, Germany’s foreign minister, cautioned Germans against traveling to Turkey and reviewed state guarantees of corporate investments made in Turkey.

Germany will also take steps to suspend negotiations to expand the scope of the EU-Turkey customs union and is reportedly considering putting joint arms projects on hold.

These steps from Germany come in retaliation to Turkey banning German parliamentarians from visiting troops participating in NATO operations in Syria and the detention of a German human rights activist for allegedly aiding a terror group.

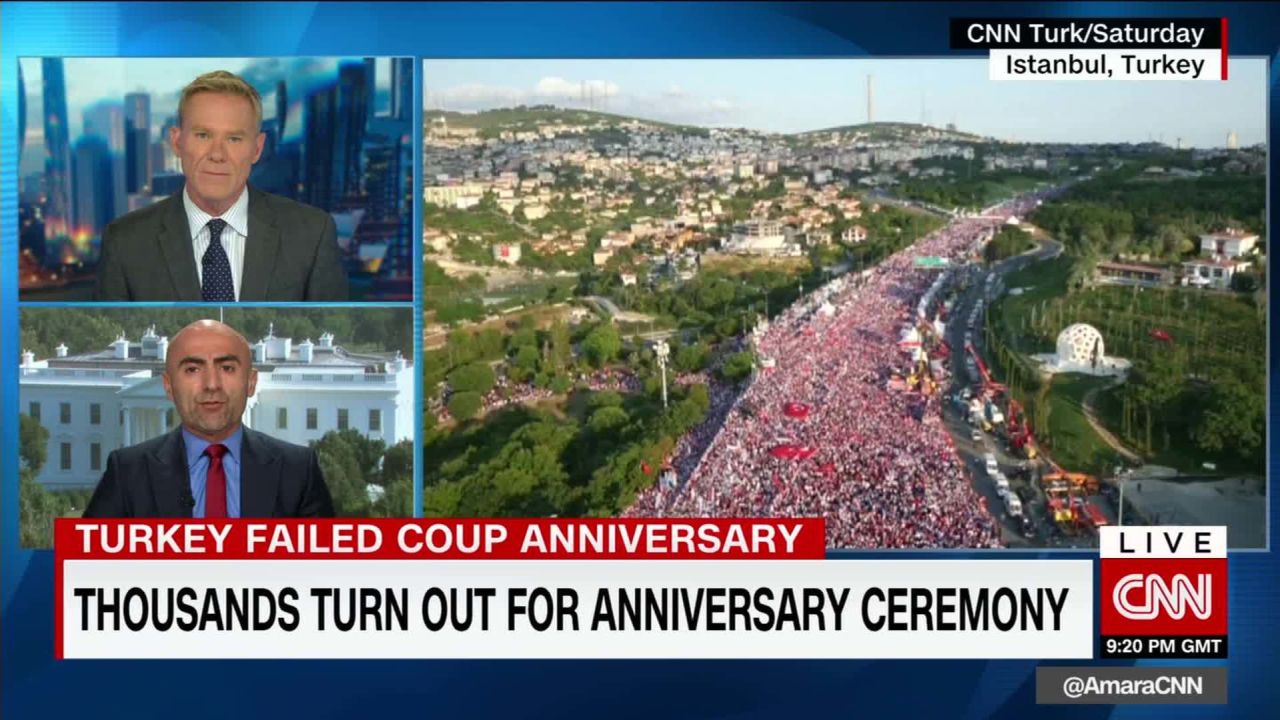

Germany, meanwhile, will likely suspect that the arrest was made to provide Turkey with a bargaining chip: Turkish state media has reported that two generals thought to be involved in last year’s failed coup in Turkey, are currently seeking asylum in Germany. It’s not hard to imagine that Erdogan would be very keen to see this pair back in Turkey.

The deterioration of bilateral relations is a reminder to Germany and the rest of Europe that Erdogan is no fan of diplomatic niceties.

It is possible that the Turkish President has misinterpreted Merkel’s desperation to secure his cooperation to stem the flow of Syrian migrants last year as a template to squeeze more money and political concessions from Europe. His strident rhetoric and uncompromising stance encouraged Merkel to cough up billions in EU money to the Turkish treasury.

Yet, it may be that Erdogan has overplayed his hand with Turkey’s largest trading partner and the dominant EU member state – in which nearly 3 million Turks reside – as the Turkish economy stagnates.

Accusing German industrial behemoths of being Gulenist supporters has forced Gabriel to advise against investing “in a country when there is no legal certainty and where companies, even entirely respectable companies, are labeled as terrorists.”

Germany’s unexpected move sends an unequivocal message to Turkey that it is rapidly losing leverage with its pugnacious foreign policy which seemingly has one primary purpose: to make Erdogan look strong at home. By indirectly expelling German troops and threatening repeatedly to terminate the Syria migrant deal, Erdogan has weakened his negotiating hand.

He has also raised concerns over Turkey’s reliability as a NATO partner and prompted Europe to put in place contingency plans in case the deal is canceled.

It is likely, though not guaranteed, that in the short-to-medium term, Erdogan will employ fiery rhetoric to set the stage for an eventual climbdown. He still retains some pragmatism and flexibility, and seems to appreciate the importance of Germany to Turkey’s economic stability.

That quality for an abrupt change of course under pressure explains, for example, Erdogan’s 180-degree turn following nine months of bitter hostility with Russia.

Nevertheless, though the dispute may eventually blow over, the longer-term implications to Erdogan’s credibility among European peers will not be easily repaired. They will probably be less keen to engage in a strategic dialogue with him or deepen political and economic ties with Turkey.

Whatever Erdogan’s mistrust of Europe, it will always represent the main source of trade, foreign direct investment and technology flows to the Turkish economy. That reality and their geographic proximity will keep them bound together in a challenging relationship – increasingly tilting to Turkey’s disadvantage.

Only the reignition of liberalizing political, economic and social reforms and the adoption of a balanced, sober-minded foreign policy can restore Erdogan’s once unbeatable reputation in Europe, the US and the Middle East.

In all likelihood, however, he will attempt to further consolidate power domestically and interfere in regional disputes, contrary to Turkey’s strategic interests.