Editor’s Note: Aaron Schulman is an American photographer, writer and editor. The following is an edited extract from his essay “The Colour Photographs by George Rodger” in “Nuba & Latuka: The Colour Photographs” by George Rodger, published by Prestel.

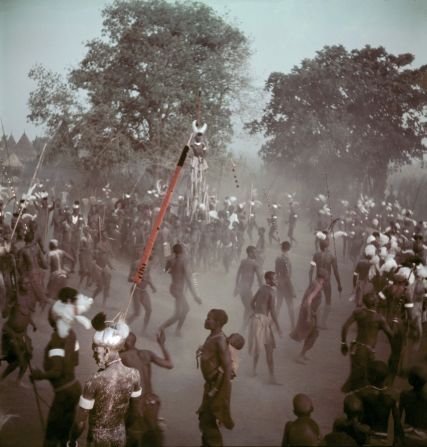

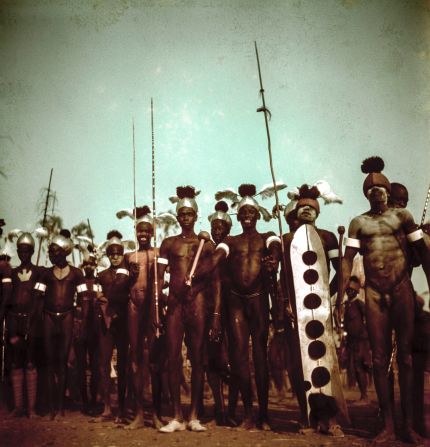

It is well established that the beautiful and beguiling black-and-white photographs made by George Rodger in 1948 and 1949 – most famously of the indigenous people of the Nuba mountains, in the former central Sudanese province of Kordofan, and the Latuka and other tribes of southern Sudan – are some of the most historically important and influential images taken in sub-Saharan Africa during the twentieth century.

Not only do they represent an array of tribes who were thoroughly unique and steadfastly traditional in terms of their customs, costumes, architecture, agriculture, rituals and social gatherings, they also document these tribes’ first authorized encounter with a Western photographer, as Rodger was granted official permission to photograph there by the Sudanese government itself.

Of course, Rodger was genuinely fascinated by the people and cultures he encountered, but as a founding member of the newly established Magnum Photos and an active contributor to the rapidly expanding international mass media at the time, he was also determined to fully convey and share his experiences of the Nuba with the rest of the world via the then dominant medium of photography.

Amongst a wide variety of interpretations, the photograph can – and often has – been too easily misconstrued as one situated within the longstanding colonial tradition of representing the people of Africa as “noble savages,” as specimens of a “primitive” humanity untouched by “civilization.”

Yet, it is important to recognize that directly prior to photographing the Nuba peoples, Rodger had spent the previous decade – from 1939 to 1947 – as a Second World War correspondent for Life magazine. In that time, he had covered the death and destruction experienced during the London Blitz, the brutality of the Burma campaign, the Allies’ violent progress through Italy, and finally the horrific piles of corpses and desperately emaciated survivors discovered at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp after its liberation in 1945, as well as much more.

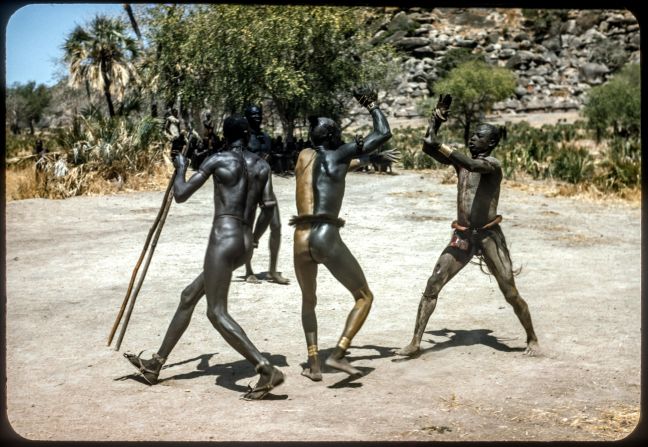

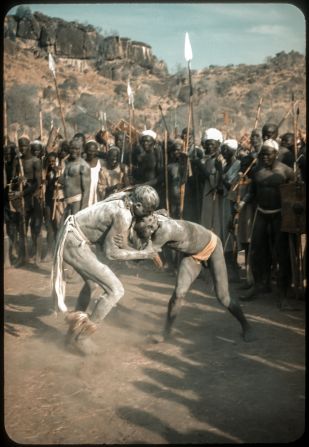

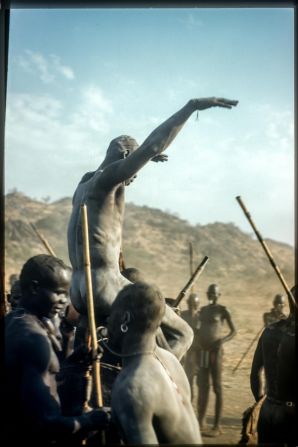

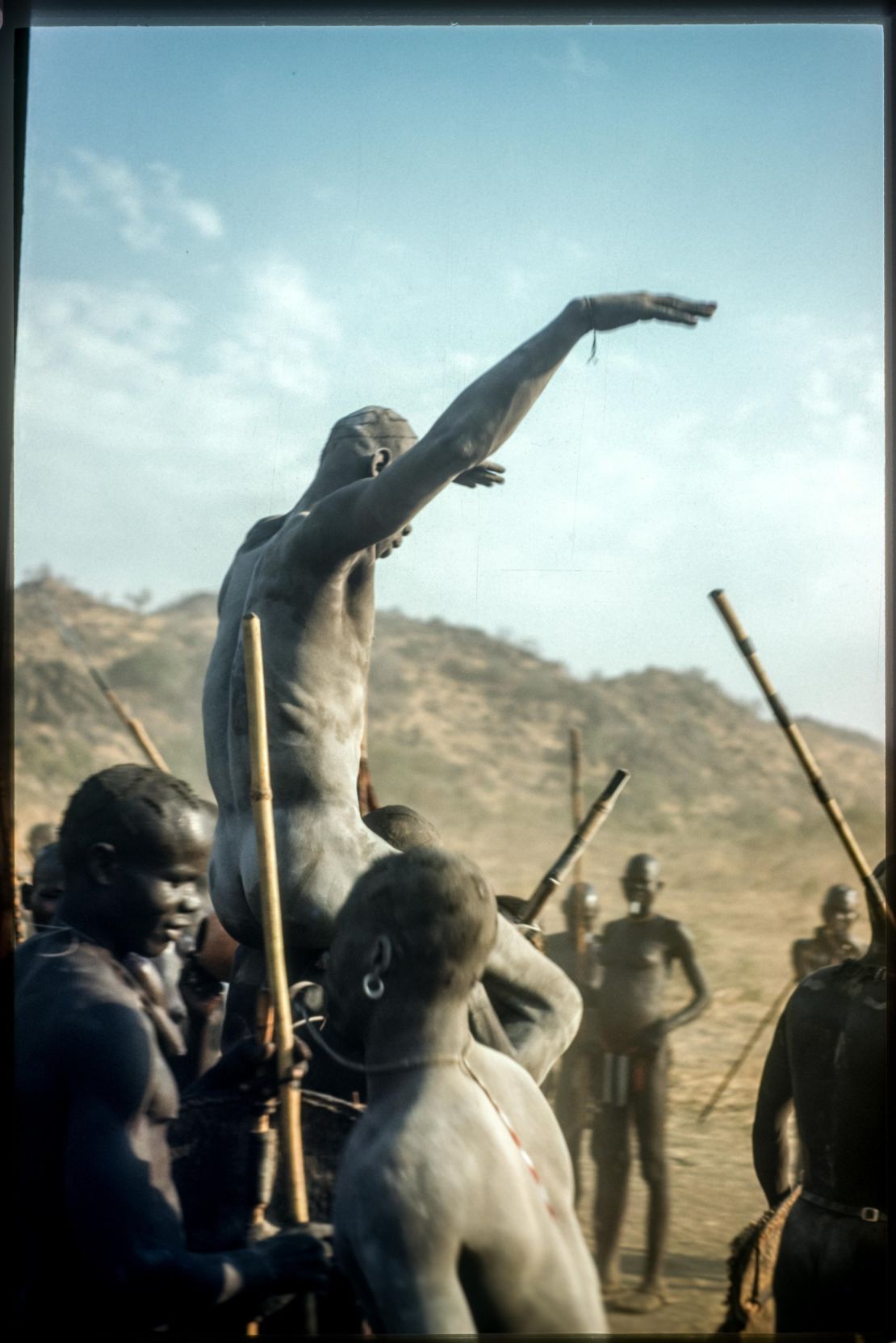

Throughout Europe and the rest of the world, Rodger had already borne witness to a level of savagery almost beyond the scope of the imagination. With this in mind, one suspects that upon encountering the Nuba he saw himself photographing something that was certainly noble but not savage, a sophisticated and civilized rather than “primitive” culture in which conflict was resolved via refereed hand-to-hand combat, and in which the victor was lifted aloft, paraded around and celebrated by the man whom he himself had defeated. As Rodger wrote several years later, “When we came to leave the Nuba Jebels (mountains) we took with us only memories of a people … so much more hospitable, chivalrous and gracious than many of us who live in the ‘Dark Continents’ outside Africa.”

Looking again at Rodger’s famous monochrome image of this wrestling champion, it is vital to remember that such photographs – despite their first impressions – are not always so black and white.

Today, much has been written and learned about the Nuba, due in large part to Rodger’s initial photographs (which first appeared in National Geographic in 1951) as well as to the subsequent and extensive photographic study, “Die Nuba,” published in the early 1970s by Leni Riefenstahl – who herself credited Rodger’s famous image of the wrestling champion as the catalyst for her own work, stating, “The artistic style of the picture, together with the expressive power of the two black Nuba, fascinated me so much that from then on I never lost my interest in this tribe. This picture changed my life.”

Yet, until now, what often distinguished Riefenstahl’s imagery from that of Rodger’s (apart from the fact that they were made several decades later; “ten years too late” according to a Kordofan police chief that Riefenstahl met during her initial search for the Nuba) was that they were printed and published in vividly striking color. Here, in “Nuba & Latuka: The Colour Photographs,” we revisit Rodger’s original 1948 and 1949 trips through a distinctly different and unfamiliar spectrum, through the unknown and previously unpublished color images that he made alongside his more famous black-and-white work.

“Nuba & Latuka: The Colour Photographs” firmly situates George Rodger within this burgeoning and important field of photographic history. Here his work in Sudan, as well as his photographic practice in general, gains even more poignancy, power and relevance as a new and dynamic dimension of his work is revealed.

These photographs help to further expose Rodger’s committed professionalism – his dedication to his own subjects, his practice, his clientele, his agency and his audience – and finally bring to light his incredible ability to capture both events and environments via the camera no matter what type of film it contained. As colorful as these newfound photographs may be, ultimately “these pictures are not photographs of color … but rather photographs of experience.”