Story highlights

Younger women with breast cancer are more likely to remove healthy breasts, a trend that varies by state, a study finds

"Sometimes, surgery is a blessing. ... It doesn't come complication-free," says a young survivor who shares her story

For many, the Fourth of July evokes jovial memories of backyard cookouts and fireworks, but for Amberlea Childs, the summer holiday conjures a haunting memory that changed her life.

Childs was diagnosed with breast cancer a day before July Fourth weekend in 2010.

She was 36, newly engaged, and had a lump the size of a large walnut in her right breast. She visited a radiologist to get it checked.

“He ended up doing five different biopsies, and on the last one, he pulled it out, and he looked at me, and his eyes welled up with water,” Childs said.

“It was definitely that out-of-body experience where you’re kind of watching your own story play out, and as his eyes welled up, he said, ‘I’m not 100% sure, but if I had to bet, I’m 99.9% sure what I just pulled out of your breast was breast cancer,’ ” Childs said.

Later on, once her diagnosis was confirmed, “I needed to have surgery.”

Childs first opted to have a lumpectomy, in which only the cancerous mass in her breast was removed, but then the disease advanced. She was told that she would need another surgery. This time, she opted for a double mastectomy, in which both of her breasts – even the one without cancer – were removed.

“I wanted to do a mastectomy on that right side, and then from there, you have to then contemplate, ‘Well, should I do a prophylactic mastectomy on the other side that does not have cancer?’ ” Childs said. “Many women have this thought, but I feel for a younger woman – and I identify as a young survivor – you have longer to live, therefore you have a greater chance of recurrence just by the mere fact that you’re going to be alive longer.”

Since her cancer diagnosis, Childs has had nine surgeries to her chest. The double mastectomy was among the earliest.

Now, she is a healthy 43-year-old Milwaukee resident and a breast health advocate with Susan G. Komen of Southeast Wisconsin. While chemotherapy treatments affected Childs’ fertility, she and her husband are preparing to adopt their first child, whom they can’t wait to meet.

“I am feeling wonderful. I can honestly say that my life is healthier, better directed after I’ve had cancer,” she said. “It gave me a different lens to look through life.”

Yet because of her experience, Childs can relate to the 7% of women with breast cancer who are diagnosed before age 40, many of whom face the same decision she did: whether to go under the knife for a lumpectomy or a mastectomy.

‘The cancer didn’t develop overnight, so pump the brakes’

Younger women with breast cancer are increasingly opting to undergo double mastectomies, even if they were diagnosed with early-stage cancer in only one breast, known as unilateral breast cancer, according to a study published in the journal JAMA Surgery on Wednesday.

The procedure to remove the healthy breast along with the affected breast is called a contralateral prophylactic mastectomy, or CPM.

In certain states, more than 42% of women 20 to 44 who underwent surgery between 2010 and 2012 opted to remove both breasts with a CPM, the study found. Researchers now are hoping to determine why.

“To be honest, I think it’s very difficult to really pinpoint why the increase,” said Ahmedin Jemal, vice president of surveillance and health services research at the American Cancer Society, who was senior author of the study. However, he offered some ideas.

“One factor that could contribute to the increase is this desire for symmetry,” Jemal said, referencing how the breasts would look more symmetrical after a double mastectomy compared with after having just one breast removed.

“Another factor is probably the Angelina Jolie effect. She was diagnosed with the BRCA-1 cancer gene that mutation that causes breast cancer, and she had a double mastectomy, so that was covered widely in the media,” he said. “For women diagnosed with breast cancer in one breast, there is no evidence to suggest to remove the unaffected breast.”

Last year, the American Society of Breast Surgeons published a consensus statement in the journal Annals of Surgical Oncology recommending against the routine use of removing both breasts in women with unilateral breast cancer – a recommendation that the American Board of Internal Medicine also made.

“CPM should be discouraged for an average-risk woman with unilateral breast cancer. However, patient’s values, goals, and preferences should be included to optimize shared decision making when discussing CPM. The final decision whether or not to proceed with CPM is a result of the balance between benefits and risks of CPM and patient preference,” the statement said.

Even if a CPM procedure is to prevent cancer from developing in the healthy breast, Jemal said, “the maximum is 6% of women will develop breast cancer on the unaffected breast within the next 10 years. It is very small.”

On the other hand, the most common second cancer in breast cancer survivors is another breast cancer, according to the American Cancer Society.

A healthy 55-year-old woman has about a 2.5% chance of developing invasive cancer in a given breast over the next 15 years, whereas a 55-year-old breast cancer survivor has a 10% to 15% chance, according to a paper published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in 2010.

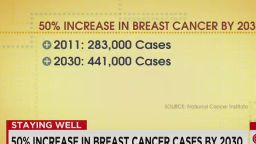

About 12.4% of women in the United States will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point during their lifetime, according to the National Cancer Institute.

“Sometimes, surgery is a blessing, and it can help remove cancer and do great things, but it doesn’t come cost-free, and it doesn’t come complication-free,” Childs, the breast cancer survivor, said.

“There is going to be time that’s needed to heal and recover, and if you’re not willing to give yourself that time, maybe you should weigh that into your decision if it was lumpectomy versus mastectomy, but I think, do the homework. Don’t rush into something so quickly. Take the time, get that extra opinion, meet with one more plastic surgeon,” she said.

“This is the best piece of advice I’ve been told and I always share with other women: The cancer didn’t develop overnight, so pump the brakes and take more time to make the best informed decision for you.”

Differences in mastectomies, by age

The new study included data on 1.2 million women 20 and older in the United States who were diagnosed with early-stage invasive unilateral breast cancer between 2004 and 2012. The data came from the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries.

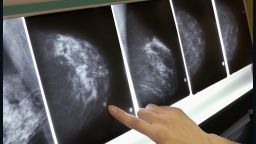

The researchers took a close look at which patients in the data underwent a lumpectomy; a unilateral mastectomy, in which only the breast with cancer is removed; or a contralateral prophylactic mastectomy.

A limitation, however, was that the researchers were unable to determine which patients may have been at a higher risk for a second cancer due to family history or genetic risk, as well as their socioeconomic status. Those factors are individually associated with the likeliness of receiving a CPM.

“Genetic testing is more commonly performed in younger women with breast cancer, and genetic predispositions are more common,” said Dr. Michael Sabel, a professor of surgical oncology and the chief of the division of surgical oncology at the University of Michigan, who was not involved in the new study.

“Many of these women may have had CPM because they harbor a genetic mutation, but I don’t think the authors had that data,” he said.

Among all the women in the study, 58.4% had a lumpectomy, 32.9% had only the breast with cancer removed, and 8.7% had both breasts removed.

The researchers found that the proportion of women opting for CPM declined with age. Only 2.4% of those 70 or older had both breasts removed, compared with 29.3% of those 20 to 29.

Nationally, the prevalence of CPMs also increased over time. Between 2004 and 2012, the number of women 45 and older who had both breasts removed jumped from 3.6% to 10.4%. For women 20 to 44, the number rose from 10.5% to 33.3%.

“It is not surprising that younger women opt for CPM compared to older. The issue is what contributes to such a decision. This trend is multifactorial,” said Dr. Francisco Esteva, a medical oncologist at NYU Perlmutter Cancer Center, who was not involved in the new study.

“For young women, they realize that they are at risk life long for a second cancer in the contralateral breast, and there is good data that the perception of this risk is greater than the real risk, but many women, with this knowledge, decide to make a definitive intervention,” he said.

By the time many women come to their surgery, they may have undergone multiple studies and interventions, which can be overwhelming, Esteva said.

“To consider ongoing higher-risk surveillance with mammograms, sonograms, possible breast MRIs, probable multiple biopsies, many benign, just becomes unacceptable and too stressful,” he said. “The women choosing bilateral mastectomy are choosing freedom from that.”

Sabel offered another idea. “MRI is more commonly performed in younger women with denser breast tissue, and we know that MRI, being more sensitive, can lead to additional findings that lead women to opt for bilateral mastectomy,” he said, but more research is needed.

“Most of the literature shows a similar pattern, with CPM being strongly associated with decreasing age,” he said. “However, this still seems particularly high in those Midwestern states, and genetics or MRI wouldn’t explain all of it.”

Indeed, the study also revealed regional differences in the rate of CPMs.

Where women are more likely to get healthy breasts removed

“What we didn’t expect was that we found the highest proportion in the Midwestern states, Nebraska, Missouri, Iowa, Colorado and South Dakota,” Jemal said.

Those are the states in which more than 42% of women 20 to 44 who underwent surgery between 2010 and 2012 opted to remove both breasts with a CPM.

The study findings also showed significant increases in the percentage of women 20 to 44 who opted to receive CPMs between 2004 and 2006 compared with between 2010 and 2012, said Dr. Deborah Axelrod, a breast surgeon at the NYU Perlmutter Cancer Center in New York. She was not involved in the new study.

“The numbers are staggering,” Axelrod said.

“In New York, for instance, which is where I practice, 11% of women in the early years had contralateral prophylactic mastectomy, which then rose to 28% in the later years,” she said. “It’s really shocking to see that dramatic of an increase.”

The trend appeared to continue across the East Coast. Axelrod pointed to Virginia, where 9.8% of younger women underwent CPMs between 2004 and 2006 and 32.2% between 2010 and 2012. In Rhode Island, 7.6% rose to 25.8%, and in West Virginia, 6% rose to 26.4%.

In Wisconsin, where Childs, the breast cancer survivor, lives, 13.8% rose to 32.7%.

Axelrod added that she didn’t think the increase could be explained on the basis of advances in developing better reconstructive techniques for mastectomies, since the rates of breast reconstruction advances did not seem to parallel the increase in mastectomies.

“The study confirms several previous studies from single institutions and from large databases showing the increase in the use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomies,” said the University of Michigan’s Sabel.

“The variability by states is very interesting and raises many questions,” he said.

Double mastectomies tripled in 10 years

Sabel and his colleagues found in a separate study that the percentage of women who were eligible for lumpectomies but opted for double mastectomies rose between 2000 and 2012. The study was published in The Breast Journal last year.

Another study, published last year in the journal Annals of Surgery, found that the use of CPM overall more than tripled in the United States between 2002 and 2012, despite a lack of evidence that the procedure offers a survival benefit.

“Further examination on how to optimally counsel women about surgical options is warranted,” the authors of that study wrote.

Join the conversation

Overall, Axelrod, the breast surgeon in New York, said that physicians should make more of an effort to have a balanced discussion with patients and try to dissuade them from removing a healthy breast without significant risk factors such as a BRCA gene mutation.

“There is a responsibility on the part of physicians to explain to women what their options are and why it’s not recommended to have the healthy breast removed, assuming that they’re in the general pool of women with breast cancer and they don’t have a mutation, and they don’t have any other mitigating factors that we look at to say ‘you are at an increased risk,’ ” Axelrod said.