Story highlights

Eggs and sperm may no longer be needed to make a baby

In 2016, researchers grew mice from eggs developed from skin cells

In the not-so-distant future, research suggests, eggs and sperm may no longer be needed to make a baby – at least not in the traditional way.

In 2016, scientists in Japan revealed the birth of mice from eggs made from a parent’s skin cells, and many researchers believe the technique could one day be applied to humans.

The process, called in vitro gametogenesis, allows eggs and sperm to be created in a culture dish in the lab.

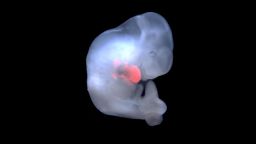

Adult cells, such as skin cells, can be reprogrammed to behave like embryonic stem cells and are then known as induced pluripotent stem cells. These cells can be stimulated to grow into eggs or sperm, which in turn are used to form an embryo for implantation into an adult womb.

Though most scientists agree we’re still a long way off from doing it clinically, it’s a promising technology that has the potential to replace traditional in vitro fertilization to treat infertility.

If and when this process is successful in humans, the implications would be immense, but scientists are now raising legal and ethical questions that need to be addressed before the technology becomes a reality.

A replacement for IVF?

In vitro gametogenesis, or IVG, is similar to IVF – in vitro fertilization – in that the joining of egg and sperm takes place in a culture dish.

But with IVF, you have to collect eggs from the woman and sperm from the man, either surgically or non-surgically, said professor Alan Trounson of the Hudson Institute of Medical Research at Monash University in Australia. “Or you can do egg or sperm donation or a combination of both.”

Trounson believes IVG can provide hope for couples when IVF is not an option.

This procedure can “help men or women who have no gametes – no sperm or eggs,” said Trounson, a renowned stem cell scientist best known for developing human IVF with Carl Wood in 1977.

Another potential benefit with IVG is that there is no need for a woman to receive high doses of fertility drugs to retrieve her eggs, as with traditional IVF.

In addition, same-sex couples would be able to have biological children, and people who lost their gametes through cancer treatments, for instance, would have a chance at having biological children.

In theory, a single woman could also conceive on her own, a concept that Sonia M. Suter, professor of law at George Washington University, calls “solo IVG.” She points out that it comes with some risk, as there will be less genetic variety among the babies.

“Solo IVG – unlike ‘natural’ reproduction – increases the possibility of homozygosity (identical genes) for recessive genes, contributing to a greater risk of disease and disability,” she wrote in a 2015 paper in the Oxford Academic Journal of Law and the Biosciences.

She added that the risk is even greater than with cloning and although you could use genetic diagnosis to find disease in embryos before implantation, it wouldn’t fully reduce the risk.

This all contributes to the fact that IVG is much more complicated than one might think, and experts add that the process will be even more complex in humans than in mice.

“It’s a much tougher prospect to do this in a human – much, much tougher. It’s like climbing a few stairs versus climbing a mountain,” Trounson said.

“Gametogenesis (in a mouse) is much faster. Everything is much faster and less complicated than you have in a human. So you’ve got to make sure there’s very long intervals to get you the right outcome. … Life, gametogenesis, everything, is much, much briefer than it is in a human.”

Most scientists are reluctant to commit to an exact time frame, but it’s probably safe to say they’re many years away.

“Most likely, we are one to two decades away from IVG being attempted in humans in a responsible, evidence-based, government-approved manner, but as we’ve seen with other new stem cell and reproductive technologies, practitioners don’t always follow the rules,” explained Paul Knoepfler, a prominent stem cell scientist at the University of California, Davis who writes a blog on stem cell research.

‘Rogue biomedical endeavors’

Knoepfler used the example of an unapproved and, he says, potentially dangerousthree-person baby produced in Mexico in 2016 by a US doctor without FDA approval.

Creating a three-person baby involves a process known as pronuclear transfer, in which an embryo is created using genetic material from three people – the intended mother and father and an egg donor – to remove the risk of genetic diseases caused by DNA in a mother’s mitochondria. The mitochondria are parts of a cell used to create energy but also carry DNA that is passed on only through the maternal line.

This process recently received approval in the UK, but it remains illegal in many countries, including the US.

“Because it seems rogue biomedical endeavors are on the increase, someone could try IVG without sufficient data or governmental approval in the next five to 10 years,” Knoepflersaid.

“IVG takes us into uncharted territory, so it’s hard to say legal issues that might come up,” he said, adding that “even other more extreme technologies, such as cloning, of the reproductive kind are not technically prohibited in the US.”

Legal and ethical challenges

For IVG to be researched further, it will be necessary to perform IVF using the derived gametes and then to study the embryos in ways that would involve their destruction. “At a minimum, federal funding could not be used for such work, but what other laws might come into play is less clear,” Knoepler said.

There are growing calls among researchers for regulators to revisit the “14-day rule,” an international agreement three decades old that says an embryo can’t be maintained in culture longer than two weeks. The “primitive streak” – a visible band of cells along the head to tail axis of the embryo – appears on day 15. Some see the rule as essentially a moral compromise between researchers and those who believe that destroying embryos is murder.

In several countries, the implantation of a fertilized egg is not allowed if it’s been maintained longer than 14 days.

Dr. Mahendra Rao, scientific adviser with the New York Stem Cell Foundation, explained that in the US, scientists can legally make sperm and oocytes (immature eggs) from other cells and perform IVF. But they would not be able to perform implantation, even in animals.

He said there needs to be clarity that this rule doesn’t apply to “synthetic” embryos scientists are building in culture, where there’s no intention of implanting them.

We may be more likely to see the first human IVG experiments performed in Asia, because laws are generally less restrictive there. The leading scientists are in Japan and China, according to George Daley, co-author of a recent editorial on the issue in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Daley and his co-authors highlight concerns over “embryo farming” and the consequence of parents choosing an embryo with preferred traits.

“IVG could, depending on its ultimate financial cost, greatly increase the number of embryos from which to select, thus exacerbating concerns about parents selecting for their ‘ideal’ future child,” they write.

Join the conversation

With a large number of eggs available through IVG, the process might exacerbate concerns about the devaluation of human life, the authors say.

Also worrying is the potential for someone to get hold of your genetic material – such as sloughed-off skin cells – without your permission. The authors raise questions about the legal ramifications and how they would be handled in court.

“Should the law consider the source of the skin cells to be a legal parent to the child, or should it distinguish an individual’s genetic and legal parentage?” they ask.

As new forms of assisted reproductive technology stretch our ideas about identity, parentage and existing laws and regulations around stem cell research, researchers highlight the need to address these thoughts and have answers in place before making IVG an option.