Story highlights

Robert Hurt and Tim Pyle turn research and data into renderings for NASA

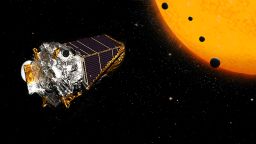

Their work resembles photographs of planets we may never see

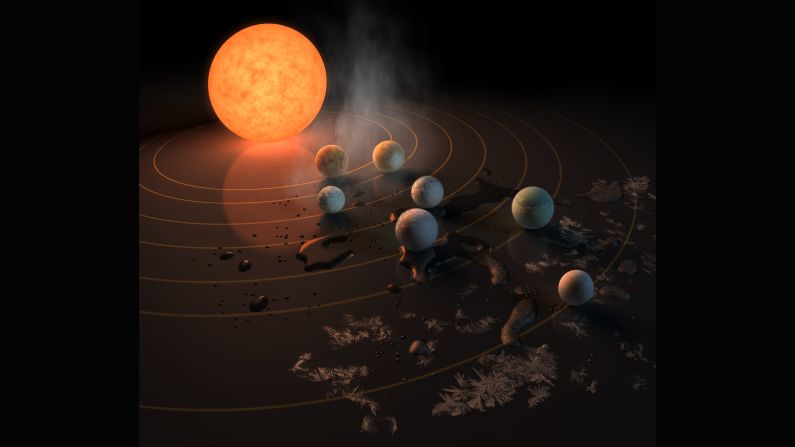

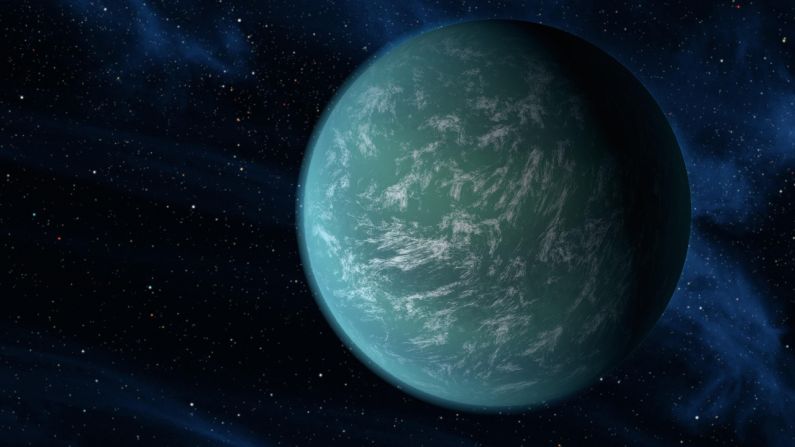

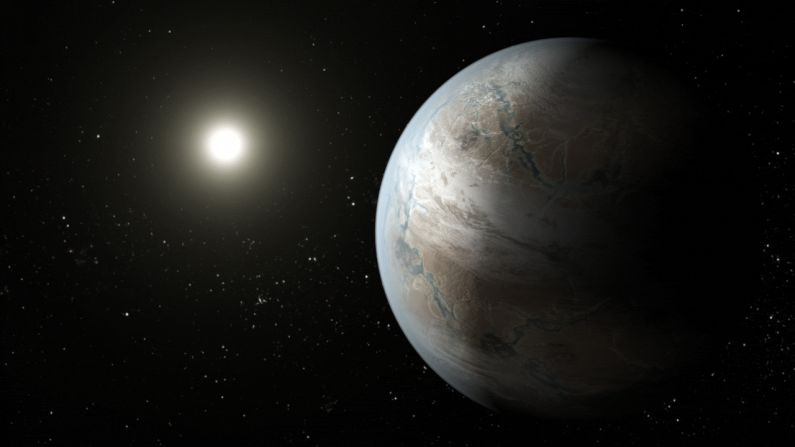

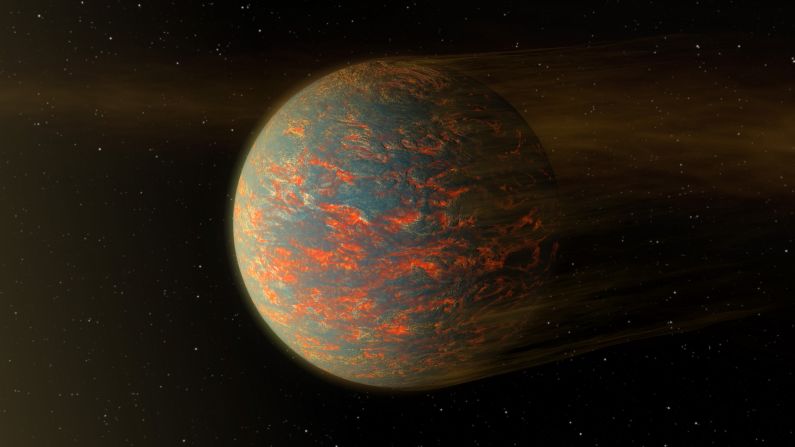

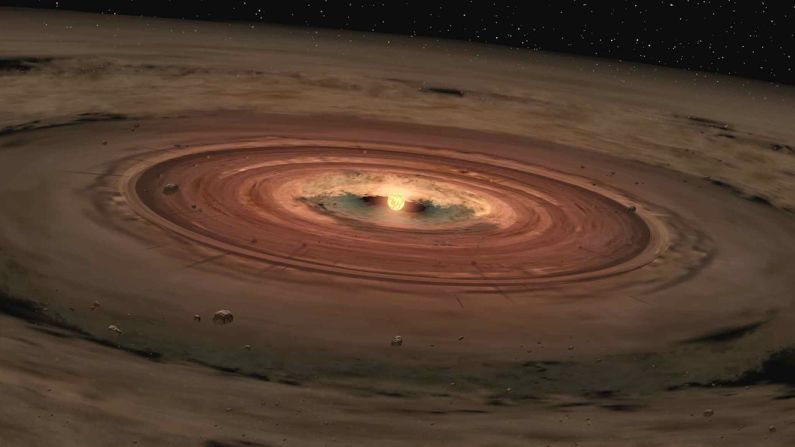

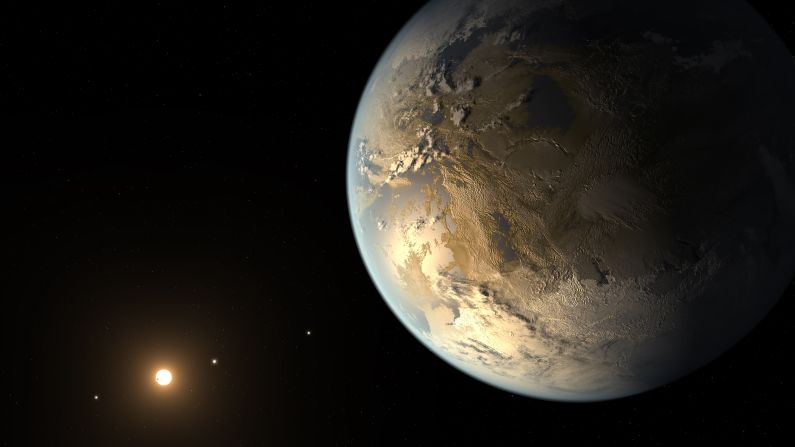

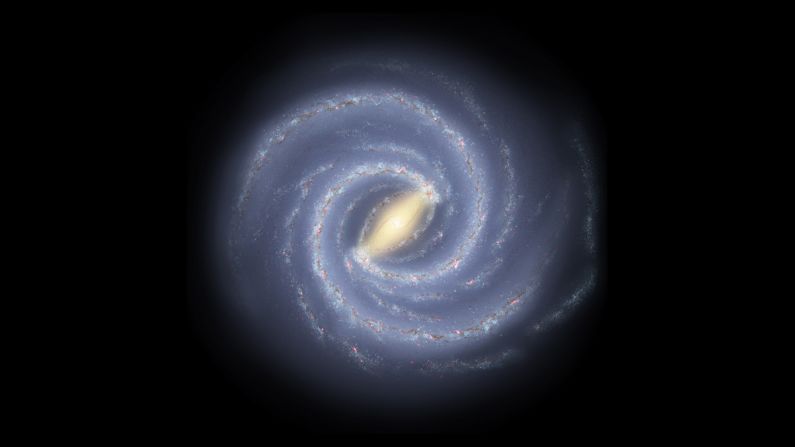

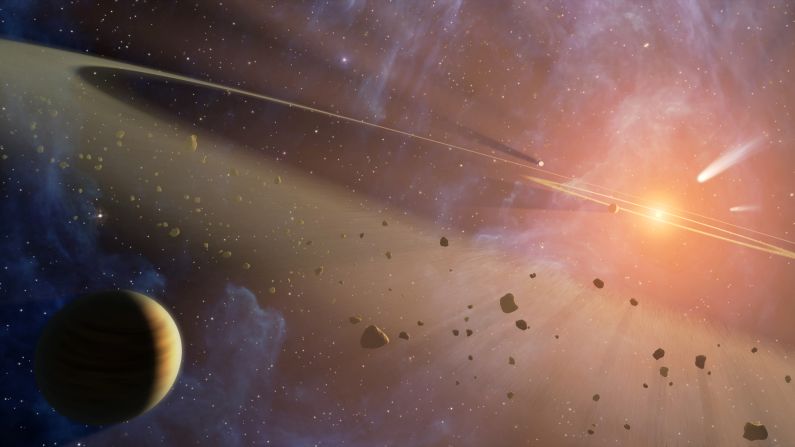

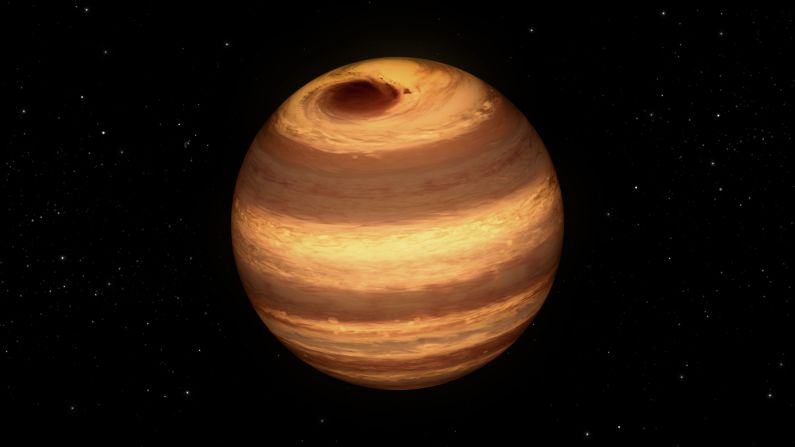

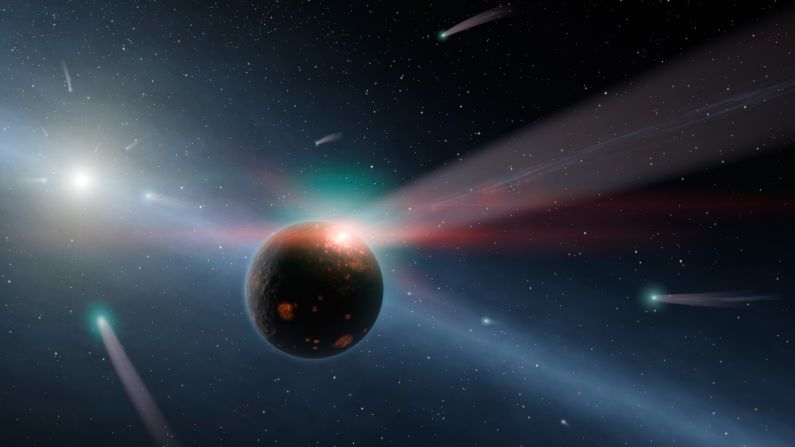

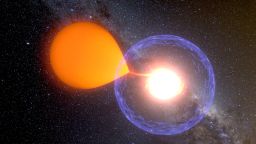

Robert Hurt and Tim Pyle have provided the world with stunningly photo-realistic glimpses at what gravitational waves, Earth-like exoplanets, rain storms of molten iron and even the Milky Way from above might look like if we could ever see them for ourselves. They also have the joy of illustrating when science fiction meets science fact, like planets orbiting two stars that harken back to twin suns setting on Tatooine in “Star Wars: A New Hope.”

They have been working together and turning study data into artist renderings for 12 years at the California Institute of Technology, the academic home of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Sometimes, they have only a little bit of lead time to produce the stunning images that accompany NASA’s news releases.

Without Hurt and Pyle, the images we associate with exoplanets would be a single pixel of light surrounded by the vast blackness of space.

“I love the fact that I get to help shape the way people see some of these NASA releases,” Pyle said.

In some cases, this even aids the scientists and researchers.

“My initial focus was not just taking data sets and making pretty images but also doing artwork and illustrations that aren’t represented visually in actual data,” Hurt said. “In spectroscopy, you’re literally breaking light up that results in a squiggly line. Even someone with a Ph.D. in spectroscopy can’t glance at a spectrum and see the significance of what that means, so turning results into an image to help people see what the story is about is part of the challenge.”

Though creating this realistic-looking artwork comes with the risk of people thinking they are actual photographs, the bar has been raised by films from the “Star Wars” franchise that present sweeping flybys of planets or the realistic representation of an accretion disc around a black hole in “Interstellar.”

“If we put out a picture that’s clumsy and dull to consciously look hand-drawn just to prevent confusion, we risk losing attention to these discoveries,” Hurt said. “Let’s make it look as compelling as it is and engage the curiosity as much as we can.”

The artist and the astronomer

Hurt took the route of an astronomer in college, and Pyle pursued film production, but both are creative and shared a love of science fiction and art from a young age.

“We sort of meet in the middle of the language of art,” Hurt said.

Before coming to NASA JPL, Pyle worked on such projects as the animated show “Invader Zim” for Nickelodeon.

Forgoing the traditional tenured professor track, Hurt wanted to be more involved in science projects as an astronomer. He got a reputation for creating photo-quality images based on the results of data sets or those he made for friends to accompany releases.

“This is the dream job I didn’t even know existed or could exist when I was in grad school,” Hurt said. “I was pursuing the things I loved doing and happened to be in the right environment, and when the need arose, and I jumped over and started doing it.”

Hurt soon found himself overwhelmed by the workload. When the job was posted, Pyle leaped at the opportunity to pursue his childhood love of illustrating space scenes.

Pyle and Hurt developed a shorthand based on their love of science fiction. When they received data from the NASA Spitzer Space Telescope or Kepler Spacecraft, one had to make only a passing mention of planets from “Star Wars,” like Hoth, Tatooine or Mustafar, and the other understood perfectly.

“I saw the original film in the theater when I was very young,” Pyle said. “For close to the next decade, ‘Star Wars’ dominated my life in terms of the toys and comics that I consumed. It’s one of the biggest reasons I pursued a career in film production.

“To me, planets around binary star systems will always be Tatooine planets. I find myself measuring molten exoplanet artist concepts against Mustafar. And I still can’t look at Saturn’s moon Minas without hearing Alec Guinness’ voice in my head, warning me ‘that’s no moon …’ “

But Hurt said that astronomers and artists such as himself are still trying to get past the “physically meaningless” representation of an asteroid field in “Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back.” Rather than being like active mine fields, asteroids aren’t typically so close together or constantly colliding. Over time, they would just turn to dust.

“Can we get past the idea that sending something through the asteroid belt is akin to throwing meat down a meat grinder?” Hurt asked.

From arrays to art

Apart from the researchers, Pyle and Hurt are some of the first to learn about new discoveries in space, like the first detection of gravitational waves or the first detection of light from an exoplanet.

“My favorite part about it is to really find out about some of the fundamentally exciting science when it is literally a secret,” Hurt said. “To be involved in the early stages before the public is aware and then have this joy of being able to shape the way that story is told is a very cool part of the job.”

The process to create a rendering is the same each time. Hurt and Pyle are briefed on the research and its findings so they can start coming up with an idea of how to represent it and whether it requires an illustration. Then, they hop on a conference call with the researchers to ask detailed questions and confirm what it may look like.

Sometimes, the scientists have concepts of what they would like to see. Other times, their conversation with the artists is the first time they’ve thought about their discovery visually. Together, they work out balancing the science with visual storytelling to represent an artistic hypothesis.

After Pyle and Hurt send a first draft back to the researchers, they usually make tweaks based on the feedback and pull together the final image.

Pyle mostly illustrates exoplanets, stars and asteroids, while Hurt’s specialties align with data coming from the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array, or NuSTAR, and depicting information around black holes.

Occasionally, they fight over who gets to illustrate certain findings. Other times, they argue over how best to represent it.

“Often, by the time we hash it all out, we end up with something better than if left to our own devices,” Hurt said.

Join the conversation

Because of their backgrounds, Hurt helps explain some of the concepts from the research to Pyle. In turn, Pyle shares graphics and animation production techniques and styles with Hurt.

“I am really appreciative of how he elevates my art, and I think I’m just grateful I have this asset that artists like me don’t have,” Pyle said.

And together, Hurt and Pyle are doing what they always dreamed and eagerly awaiting the next exciting discoveries they get to illustrate.

“I’ve been delighted to have the chance to connect my personal love of science fiction to my profession of communicating the amazing science being done that is starting to connect what we know to things that we’ve only dreamed about,” Hurt said.