Story highlights

The less you make, the more you stress, which may shorten your life expectancy

A widening income gap in America seems to drive this disturbing health disparity

Can money really buy happiness? Experts aren’t so sure, but a new paper suggests that it can buy less stress and a longer life.

Higher-income Americans are twice as likely to report being in good health than their lower-income counterparts, and they are less likely to have high stress levels, as seen in an index of blood pressure and other biomarkers, according to the paper, which was released by the Brookings Institution’s economic policy initiative The Hamilton Project on Monday.

However, the paper also showed that Americans at all income levels have higher levels of stress than they didfour decades ago and fewer Americans have reported being in very good or excellent health.

“We were surprised that health appears to be deteriorating for people across all income groups, though the change is more pronounced for those with low incomes,” said Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, director of The Hamilton Project, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a co-author of the paper.

“We don’t know for sure which aspect of income drives the differences that we find, because income is closely tied with many aspects of life,” she said. “For example, income insulates individuals from chronic stress associated with food insecurity, violence and substandard housing and also provides better access to high-quality health care.”

The poor are more stressed than the rich

Schanzenbach and her colleagues analyzed data on Americans’ incomes, body mass indexes, stress loads and self-reported health and well-being. The data were collected from 1976 to 1980 and 2009 to 2014 as part of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

The researchers divided the overall distribution of income for each year in the data into thirds: lower, middle and high income. Then, they took a close look at each income group’s health reports, obesity and stress load.

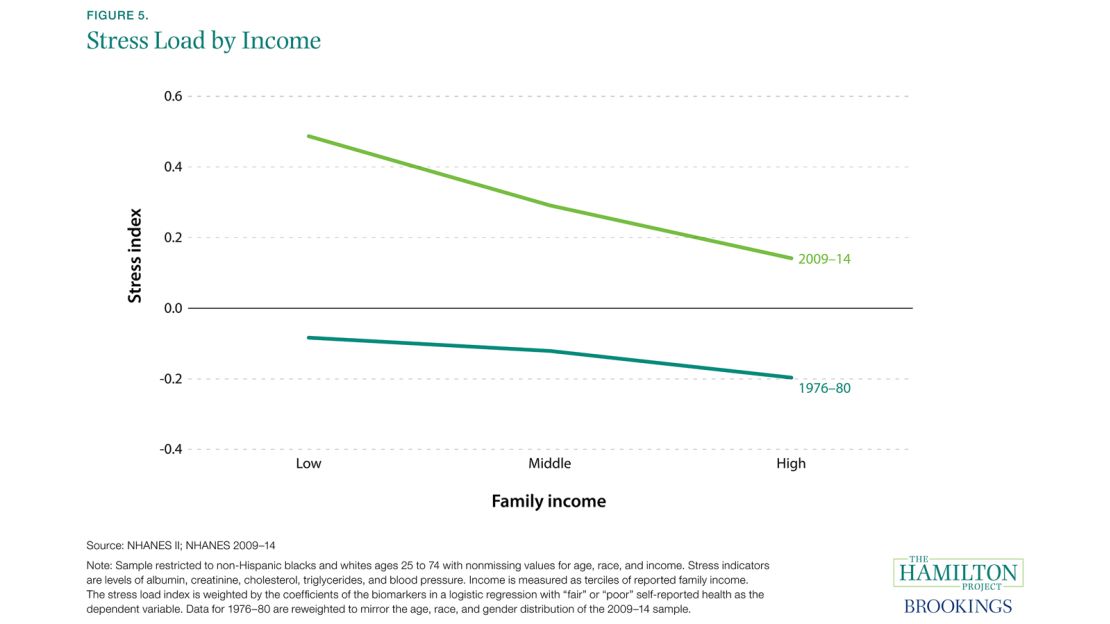

“We measured stress load as a composite of commonly used biomarkers: blood pressure, cholesterol, triglycerides, creatinine (kidney function) and albumin (liver function). These are important biomarkers for health, and they are measured in both 1976 to ’80 and 2009 to ‘14,” Schanzenbach said.

It turned out that the likelihood of Americans reporting that they’re in very good or excellent health was directly linked to their income for both time periods, the researchers found.

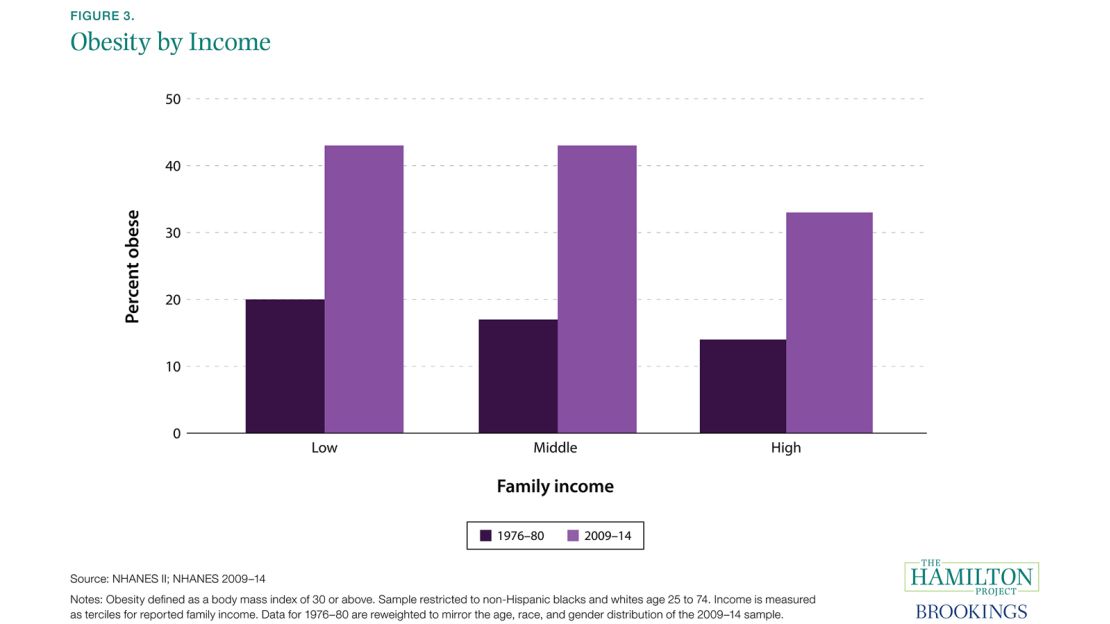

For instance, although rates of obesity have increased for all income groups in the past 40 years, the data showed that those with higher incomes were less likely to be obese than those with middle or lower incomes in 2009-14.

Overall, stress has increased among Americans since 1976, but the data also showed that those with higher incomes had lower stress loads, regardless of the time period.

However, income was more closely related to stress in 2009-14 than it was in 1976-80. Therefore, lower-income Americans experienced a larger increase in stress from 1976 to 2014 than higher-income Americans.

Schanzenbach said she was surprised to find in the data that the number of younger Americans reporting excellent or very good health declined by more than 10 percentage points between the 1970s and 2014. In contrast, the share of adults age 50 to 74 reporting excellent or very good health increased since the 1970s.

“This paper documented some new facts about how health has changed over time by income and age. Unfortunately, we are limited in the number of factors we could investigate. For example, we would have liked to investigate depression and other mental health measures as well,” Schanzenbach said.

“In addition, we cannot say for sure what are the underlying causes of these changes. Understanding the causes deserves much more study,” she said. “We hope to conduct follow up studies along these lines and also hope that our results spur other researchers to investigate these questions as well.”

Stress and status

A higher income can lead to having greater access to resources that benefit individual health, which may explain the income-health disparity, said Mark Rank, a professor of social welfare at Washington University in St. Louis, who was not involved in the new paper.

“Overall, the findings in this paper are consistent with a large volume of research which has shown that income is strongly related to health status and that stress is also strongly related to health status,” Rank said.

“I would argue that the relationship between income and health disparities is largely related to differences in resources and levels of stress across income groups,” he said. “Living in poverty creates an extreme amount of economic, emotional and physical stress. These, in turn, lead to a greater likelihood of worse health – both physical and mental health. In addition, those with lower incomes are less likely to have access to the health care system, which results in worse health outcomes.”

Rank said that mounting stress and anxiety from economic insecurity probably played a role in increasing the country’s death rate.

Data released by the CDC last week showed that overall life expectancy in the US has dropped for the first time since 1993.

Join the conversation

“More and more Americans in recent times have been struggling economically. There is much greater economic insecurity, vulnerability and anxiety among the working-age population. This is indicated by a wide range of economic trends and patterns,” Rank said.

“My argument is that one result of this is that such economic anxiety takes a toll upon life expectancy,” he said. “Although it is always difficult to establish causality, I believe that a strong argument can be made that many Americans are suffering with respect to their health as a result of the current economic woes that many people are experiencing. This is consistent with the overall findings in the Hamilton Project study.”