Story highlights

Oldest known sample of the variola virus has been found in the DNA of a child mummy

This latest research suggests that smallpox is much more recent than we might think

The oldest known sample of the smallpox-causing variola virus has been found within the DNA of a 17th-century child mummy. The mummy was found in a crypt beneath a Lithuanian church, according to a new study in the journal Current Biology. The finding shortens the timeline for how long smallpox may have afflicted humans.

Smallpox, a contagious and sometimes fatal infectious disease, is the only human disease to be eradicated by vaccination. It is also the first disease that a vaccine was developed to combat.

The disease has previously thought to have affected humans as far back as ancient Egypt due to pockmarked scarring on mummies that are 3,000 to 4,000 years old. But researchers knew that smallpox may not be that old; that type of scarring can also be associated with chickenpox or measles, according to study co-author Hendrik Poinar, director of the Ancient DNA Center at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario.

This latest research suggests that smallpox, which was eradicated in 1980, could be much more recent.

“This study suggests that all 20th-century variola strains and our 17th-century strain share a common ancestor in the late 16th century or early 17th century, which is more recent than we would expect for a virus that has supposedly been afflicting humans for millennia,” said Ana Duggan, lead study author and post-doctoral fellow at the McMaster Ancient DNA Center. “However, this date correlates with historical records which show that there is little suggestion of epidemic smallpox in Europe before the 16th century.”

Duggan added that there is a lot of uncertainty around our understanding of smallpox, including how the virus developed or when it began infecting humans. But this study is helping to establish an updated timeline of smallpox at a time when exploration, migration and colonization could have helped to spread the virus.

The researchers were also able to use this timeline in conjunction with other data to identify more information about the evolution of smallpox. When Edward Jenner developed his vaccine in the 18th century that would eventually lead to its eradication, the data shows that the variola virus split into two strains.

“There is some historical evidence that increasingly widespread inoculation in England during this period may have converted smallpox from a disease largely of adults to one of infants,” the researchers concluded in the study.

Duggan and her team first learned of a mummy with the initial indication of a smallpox infection through a collaboration with researchers in Lithuania and Finland. It had been recovered from the crypt of the Dominican Church of the Holy Spirit in Vilnius, which overlies a number of subterranean chambers which hold mummified and skeletonized human remains of both clergy and laypeople.

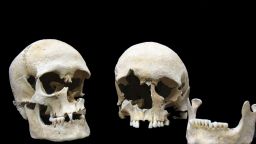

The mummy consisted of the partial remains of a child, between 2 and 4 years old, who was thought to have lived between 1643 and 1665. They extracted DNA from a skin sample, saw the potential signs for variola virus DNA and used a specific target-enrichment to extract the specific molecules for a closer look. The World Health Organization gave the researchers permission to study the DNA.

But they know little of the mummy itself, including its gender, due to the circumstances of its environment. Since the early 19th century, the site and its mummies were most likely disturbed, according to Italian bio-anthropologist Dario Piombino-Mascali, a visiting researcher at Vilnius University. The crypt was said to be host to the alleged Napoleonic burial in 1812, a deposit of other uncategorized human remains and even served as a bomb shelter during WWII.

Join the conversation

“The crypt and its stories are part of the local folklore, and a number of ghostly tales and other anecdotes began circulating already in the mid-19th century,” he said.

Most of the remains are in one cellar, and after the installation of a glass window that changed air flow into the crypt, many of the mummies began to decompose, Piombino-Mascali said. Church officials requested an investigation to enable documentation, study and curation of 23 human mummies in the crypt. Now researchers like Duggan can use the data from the tissue and bone sample records.

“Ancient DNA gives us these extra internal calibration points. We get an extra dimension of time in our research, checking in on biology long after death,” Duggan said.