Story highlights

The Dengvaxia vaccine has been licensed for use in six countries

A study warns that it could increase cases of severe dengue if used in low-burden areas

This may go against what typically comes to mind when you think about vaccines, but the newly licensed vaccine against the dengue virus – trade name Dengvaxia – could lead to an increase in the number of cases of the disease if not implemented correctly, experts warn in a new study.

The number of people affected by dengue has increased in recent years, with 390 million people estimated to be infected each year, and cases of the disease have become more global – with cases reported in more than 100 countries worldwide.

The long road to a vaccine

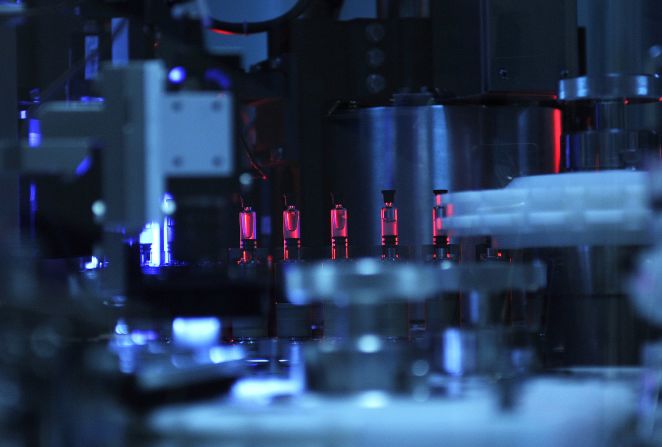

Dengvaxia was produced by Sanofi Pasteur, which, after spending 20 years developing the vaccine, published promising findings on its effectiveness in 2015. Trials showed the vaccine to be 59.2% effective against dengue when results were pooled across populations and age groups, though this varied when looking at the type of dengue, the age of those receiving the vaccine and whether people had been previously infected.

“It’s effectiveness depends on the local epidemiology of dengue and how intense the transmission is,” said Neil Ferguson, director of the MRC Center for Outbreak Analysis and Modeling at Imperial College London. “If you vaccinate people at high risk and in the right age group, you can get significant benefits.”

The vaccine is now licensed for use in six countries; in April, the Philippines became the first to roll it out. Brazil recently announced plans to implement the vaccine, and Paraguay, Singapore, El Salvador and Mexico are due to follow suit, as they all have high burdens of the disease.

But in the new study, published Thursday, Ferguson used data from the clinical trials to assess the impact of using the vaccine in different settings and found that its use in areas with low levels of disease, where people are unlikely to have been previously exposed to dengue, could lead to an increase in people severely affected by the infection due to the complexities of the virus and the way it interacts with our immune system.

The severity of coming second

“Unlike most diseases, the second time you get dengue, it’s much more likely to be severe than the first time you get it,” Ferguson said. When people who have never experienced the infection get immunized, the vaccine may act like a silent infection, gearing them up for a more severe infection should they face the real form of the virus.

“The immunity we develop both protects us and places us at risk,” said Derek Cummings, professor of biology at the University of Florida, who co-led the study.

“It can have the potential to make things worse if it’s misused,” Ferguson said.

The reasons behind this unique biology come down to the virus’ effect on the human immune system. When someone first becomes infected with dengue, they experience mild flu-like symptoms while developing antibodies. But when the person becomes infected again, though antibodies will recognize the virus particles, they are unable to neutralize the virus and instead help it enter the person’s cells to cause a more severe form of the disease, known as antibody-dependent enhancement.

“You’d have increases in hospitalized dengue cases,” Cummings said. “It would be exactly the opposite of what you intend to do.”

The models in the study found that the long-term impact of the vaccine, even when used in high-burden settings, is likely to reduce cases of dengue by just 10% to 30% due to this tradeoff between reducing cases in some places and increasing cases in others.

Testing before vaccinating

Both Ferguson and Cummings believe the risk of the vaccine leading to severe cases of the disease in some could beremovedwith the development of serological tests for previous exposure to dengue before people receive the three-dose vaccine. The idea would be to vaccinate only those who have been previously exposed, and potentially with just one dose.

“This vaccine is fantastic [for people] who have seen dengue in the past,” Cummings said. If it’s used only on these people, “then this could be an extremely effective public health campaign.”

This form of screening would, however, mean people who have never been infected would miss out on the vaccine, but also the risk that comes with it – at least until they become exposed.

The study found that vaccinating people who have been exposed in the past would reduce their risk of being hospitalized with dengue by more than 90%.

“[This analysis] places even greater emphasis on targeting this new vaccine to the right people at the right time and echoes the increasing scientific consensus that countries should be considering wide-scale testing before deploying the vaccine,” said Oliver Brady, research fellow in mathematical modelling at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, who was not involved in the research. “Serological testing for past infection at the population, or even individual, level needs to be reconsidered by every country deploying this vaccine.”

But he added that making this distinction in countries where Zika is now spreading could make things more complicated. Similarities between the two viruses mean such tests may result in false positives. “As a result, there is greater chance of vaccinating people who may have long-term negative impact from the vaccine.”

But this is not a concern for now, as no test exists to screen people in this way.

In the meantime, the team is advising policy-makers and program implementers to follow guidance when rolling out the vaccine, for example, by identifying which communities have the highest transmission rates and focusing on them, or vaccinating children at an older age to increase their likelihood of having been previously exposed.

Brady added that the team may also be too presumptuous that the effectiveness of the vaccine is driven solely by whether people have been infected. “One alternative interpretation of the trial data would be that vaccine efficacy and/or disease severity could vary by age,” he said. “It may simply be that this vaccine is not suitable for use in children under the age of 9.”

Prioritizing those at most risk

The need to focus on communities with a high burden of the disease is echoed in the WHO Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization’s recommendations for implementing the vaccine.

Join the conversation

The WHO said it has been working with modelers, including the study authors, since April 2015 to predict the public health and economic impact of a vaccination program.

The organization endorses the need to develop tests to identify people most likely to benefit from the vaccine and says individual testing could be possible, especially in lower-burden countries with the proper resources and infrastructure.

“This vaccine is not a silver bullet for dengue,” Ferguson said. “The most important thing is for policy-makers in these countries to be well aware of the benefits and risks and to set correct expectations among the public … as people may conclude the vaccine doesn’t work.”