Story highlights

Must Farm is the site where an almost year-long archeological dig has been taking place

The exploration has unearthed a well-preserved Bronze Age settlement and revealed incredible facts about a lost time

British archaeologists working on the Must Farm project in England’s Cambridgeshire Fens can hardly restrain themselves.

Their online diary effervesces with superlatives – “truly fantastic pottery,” “truly exceptional textiles,” “a truly incredible site,” “the dig of a lifetime.”

Typically on prehistoric sites, you are lucky to find a few pottery shards, a mere hint or shadow of organic remains; generally archaeologists have to make do, have to interpret as best they can.

But this archaeological dig has turned out to be completely, thrillingly different.

For the last ten months – day by day, week by week – the excavation has yielded up a wealth of astonishing finds including pottery, textiles, metal work and ancient timbers. The dig offers, as site manager Mark Knight from the Cambridge Archaeological Unit put it, “a genuine snapshot” of a lost world – a prehistoric settlement from the Bronze Age some 3000 years ago.

The dig is almost without precedent the most revelatory of its kind in Britain, if not in Europe, and it has already begun to transform our knowledge of life in the Bronze Age.

Jointly funded by the the government sponsored heritage organization, Historic England and the managers of the clay quarry, Forterra, the dig has been carried out under a large rectangular white tent – about a thousand meters square. It’s the sort of tent you might use for a wedding reception but here it’s perched on the edge of a working quarry. Far below, a big crane is busily extracting clay to make bricks.

READ MORE: Sunken city reveals secrets of a lost Egyptian city

The archaeologists arrived in force last September and, protected from the wind and rain under the tent, they’ve been forensically digging away several meters below sea level. Interest was first aroused in 1999 when a series of wooden posts were discovered sticking out of the clay. Trial excavations followed in 2004 and 2006 when Bronze Age spearheads and a sword were found.

All very promising but still no one realized quite what they’d stumbled on.

Britain’s Pompeii

The site has been described as the British Pompeii.

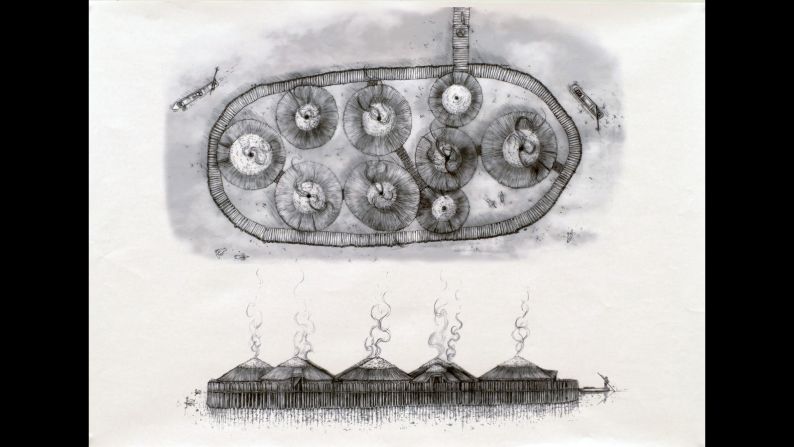

Of course, the Roman town-city was much larger (a plot of over 60 hectares with a population of approximately 11,000). Here in the English Fens, it was just a small river community of 30 or so people living in nine or ten wooden round houses erected on stilts on a platform by the water. But both places are relics of single dramatic events.

Pompeii was buried in a volcanic eruption in 79 AD. The Bronze Age settlement at Must Farm was destroyed just as suddenly and violently by fire a thousand years earlier. The blaze took hold on a summer’s day and may well have burnt itself out in less than an hour. The round houses – of wattle, reed and timber – and their contents collapsed into the water and more importantly, into the river silt. It’s the speed of the event – the brevity of it, the almost instant entombment of the material – that makes the find so exciting.

Much of what was tipped into the water is in pristine condition. It’s as if the archaeologists have arrived just after the fire, rather than 3000 years later. They’ve found pretty much everything they could have ever hoped for.

The Bronze Age Man

The truth is we didn’t know that much about ordinary Bronze Age man. But according to Cambridge Professor of Archaeology Cyprian Broodbank, it now seems entirely possible that there may have been “a mosaic of thriving communities” scattered along the waterways across the English Fens, and that the people living there were much more sophisticated than previously thought.

We know they had log dug-out canoes, ranging in length from three to nine meters (eight examples, mostly of oak, were found nearby in 2013).

We have already learned more about their diet – featuring a menu of wild boar, red deer and freshwater fish similar to pike. They also had farm animals, lambs and calves.

In time, as the newly discovered artifacts are microscopically examined, we will learn more about how they lived and traded. Beads (some 60 of them, apparently from necklaces) have been found made of glass, amber and jet and seem to originate from the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East – possibly from Syria or Turkey.

We will learn more about what they wore – some of the textile fragments (about 80 pieces, including linen) are very finely weaved and a cluster of footprints was discovered in the silt from which shoe sizes can be determined.

Unlike Pompeii, there are no skeletons. The only human bone found was a trophy skull; it apparently hung on the outside of one of the round houses.

There is an unprecedented abundance of burnt timber to analyze (some 4,000 pieces). It’s probable that we will find out what caused the fire – initial forensic research suggests it may have been started deliberately.

Domestic bliss in the Bronze Age?

What has already emerged at Must Farm is a sense of cosy domesticity. Of the five round houses excavated, each had a set of about a dozen pots – simple, plain and beautifully hand-made.

They range in size from little poppyhead cups a few centimeters across to storage pots up to 35 centimeters high. Some still contained food debris – a cereal porridge of some kind.

Bronze Age man farmed the land, managed the woodland. The archaeologists believe the ash palisade – the protective fence encircling the settlement – was harvested from a coppice planted some 20 years earlier.

They were skilled carpenters – they ate off wooden plates; they carved wooden boxes.

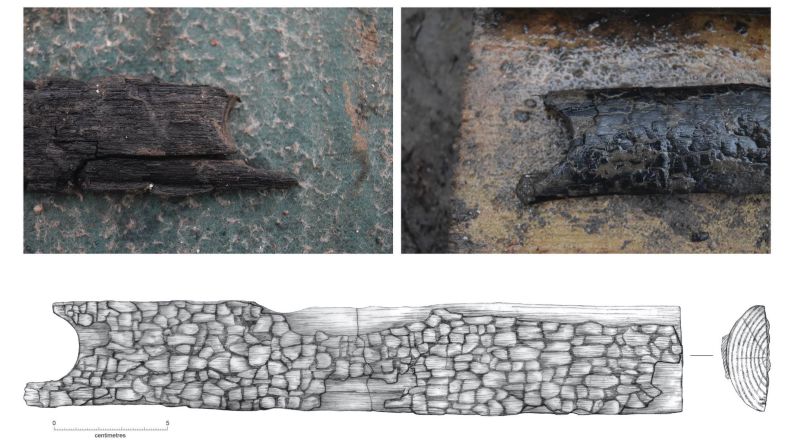

A prized discovery was the almost perfectly preserved wheel of a wooden cart. And they left us their most treasured bronze possessions –15 axe heads, five sickle heads and five spear heads. In one of the rarest finds, a spear head was found with its haft or handle still in tact.

READ MORE: Did ancient Egypt suffer from climate change?

Archaeologists now also know precisely how the round houses were built.

They have the architecture – the wattle, the uprights, the posts. You can see the axemarks. One palisade timber – sharpened to a point like all the others – is still girdled by a piece of Bronze Age rope. Singed roof timbers were found splayed out in the mud like radiating spokes from an umbrella – the circular footprint of each round house. With the right will and adequate funding, they could accurately make a replica of the settlement as an open-air museum in the Fens.

See inside a Bronze Age village

Hidden details, revealed

Since the dig began last September, I’ve visited Must Farm three times. And with each visit the story has become more detailed, more enthralling.

Knight, told me excitedly on my first visit that he was preparing to step inside a Bronze Age round house. Now he has – and not just one but four or five. He is still marveling at it all: “I think I’ve found a landscape that has a story,” he says, “a landscape that hasn’t been described before, hasn’t been visited before. We are the first people to explore it.”

The archaeological site has extraordinary clarity, cogency and intimacy.

You can easily imagine what it was like for our ancestors 3000 years ago. Running across one part of the site is a narrow wooden causeway, a series of oak planks less than a meter across. Pre-dating the settlement, it rests there invitingly – cleaned of mud and silt – waiting for us to follow in our ancestors’ footsteps.

Inside the tent, watching the team of archaeologists working away on their hands and knees, I also sensed a feeling of unresolved mystery. This is a Bronze Age story without a happy ending. We now know that the oak trees used for building the roundhouses were felled in winter.

The settlement burnt down the following summer barely six months later; it hardly had time to establish itself. Was it attacked? Had the settlers intruded onto someone’s else’s river bank ? Was the settlement razed because of disease or out of superstition?

What is clear is that no one came back to salvage precious belongings from the shallow sediment. Only now, all these years later, have they been retrieved from the dark clay almost as new.