Story highlights

Green extracts have shown to improve performance in certain brain regions relating to memory

A recent study also found green tea could treat certain symptoms of Down Syndrome

The images that come to mind when thinking of green tea are likely associated with calmness, purity and relaxation.

The ancient beverage has been used for centuries in Chinese medicine as a means to relieve people from various ailments, but more recently the tea – and its extracts – have caught the attention of scientists. Teams across the world have been trialling green tea extracts and specific compounds within them for their potential to lower the risk of various conditions: cancer, blood pressure, cholesterol and even Alzheimer’s disease.

Evidence for these benefits is limited, however, and often inconclusive, but recent studies have found that one particular compound inside green tea, known as EGCG, could improve the functioning of one particular part of the body: the brain.

Boosting brain power

“Many people consume green tea extracts in some form, so we were interested in the effects [on the brain],” said Stefan Borgwadt, Professor of Neuropsychiatry at the University of Basel.

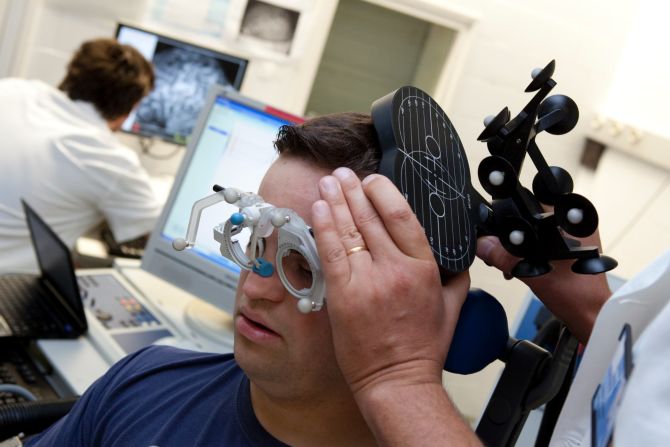

In 2014 study, Borgwadt’s team gave green tea extracts to 12 healthy volunteers and imaged their brains to see changes in connectivity inside certain brain regions. The volunteers were given beverages containing extracts equivalent to one or two cups of green tea. They consumed them nasally to ensure their tongues couldn’t taste whether the drink contained the extracts.

After four weekly doses of the drink, the team saw increased connectivity in regions of the brain associated with working memory.

“Drinking green tea improved memory in healthy people,” said Borgwadt who stresses the small scale of the study and the associated limitations of their findings, but the team saw promise in the results.

“As it is a more natural kind of medication, [people] are more likely to change it,” he said. “It could be helpful for diseases.”

Since this research, interest in the cognitive benefits of green tea has grown and focused on the potential to improve symptoms of certain neurological, or psychiatric, disorders.

“There can be plasticity changes in the brain,” said Mara Dierssen, Group Leader of the Systems Biology Group at the CRG-Center for Genomic Regulation in Spain. These changes can be used to target diseases such as dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, but Dierssen has long been searching for ways to treat one particular condition – Down syndrome.

“[People thank] there is no hope and that people with Down syndrome cannot be treated due to its complexity,” said Dierssen.

But she has set out to prove them wrong.

Taking on Down syndrome

Down syndrome is a genetic condition caused by people having an extra copy of chromosome 21 and is estimated to occur in 3000 to 5000 children born globally each year.

The presence of the extra chromosome means people with the condition have more genes being expressed in their cells – and more proteins being produced – resulting in a range of physical and intellectual disabilities. These include decreased muscle tone, a flat face, slanted eyes and a range of potential learning disabilities.

“A number of genes are overexpressed and there is no way of tackling this overdose of genes,” said Dierssen. Her team set out to find out any genes that contribute more greatly to the disease itself and found one key player, called DYRK1A.

“This gene causes a lot of the neurological and [physical] symptoms of Down Syndrome,” she said.

By controlling the activity of this gene, and the proteins it expresses, the team could reduce some of the cognitive symptoms of the condition and the contender to have this control came in the form of the EGCG compound found commonly in green tea.

The tea potential

In a recent study, Dierssen’s team analyzed the potential for EGCG to improve symptoms of Down Syndrome in 87 people with the condition, with half receiving 12 months of pills containing the compound and the other half given a placebo. All participants received cognitive training as well.

Those given EGCG performed better in tests for visual memory, the ability to control responses and the ability to plan or make calculations. Brain scans revealed improvements in connectivity between nerve cells and improvements were also seen in areas of the brain relating to language.

“This shows we can really target Down syndrome pharmacologically,” said Dierrsen. For some patients, the effects lasted an additional six months after the study ended.

“This [study] confirms that you can give these extracts to have beneficial effects,” said Borgwadt. “We need to know if these affects are specific for Down syndrome or if it is a more general effect on brain diseases.”

Dierssen stresses this is not a cure for the condition as all of the neurological changes caused by the condition cannot be overcome. “What we see is that we can improve functionality,” she said.

Borgwadt added it would be far too optimistic to expect this to become a treatment for the disease as the size of the effect is unclear and patients with the condition experience a range of symptoms. “You see effects, but are they fully relevant to the patient?,” asked Borgwadt.

The team also saw a difference between genders, which they will provide greater insight into in their next paper, but for their discovery to have true effect, the team must next trial the green tea compound in greater numbers of people.

“Let’s hope that the promise of this early experimental study is confirmed in larger-scale trials,” said Professor David Nutt, Head of the Centre for Neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London in a comment. “Others follow[ing] this approach as therapy targeting a number of the biochemical abnormalities that result from trisomy 21 might be the most effective way forward.”

Experts are also quick to highlight that simply drinking green tea will not help.

“We cannot recommend that people self-medicate with green tea because different varieties contain different levels of the key compound,” said Dr Marie-Claude Potier, Researcher on Down Syndrome and Neurodegenerative Diseases, Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle.” It’s also vital that we see the results of a toxicity study with these nutraceuticals before going further.”

They next plan to also test the compound in children where there could be greater effect as the brain is more adaptable at younger ages. “We hope there will be more improvement in children,” said Dierrsen.

The findings have also inspired experts like Borgwadt who are curious about any benefits against other neurological diseases.

“One could argue there is a more general affect of neuroprotection in the brain, so it could help other psychiatric diseases,” he said.