It’s early evening and you’re with friends, enjoying a drink or two. The sun is shining after all and it’s been a long week.

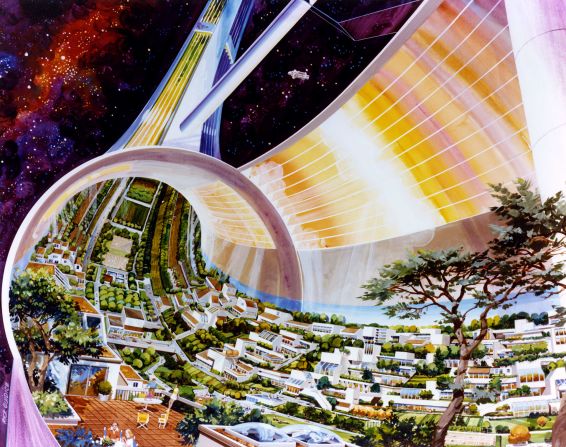

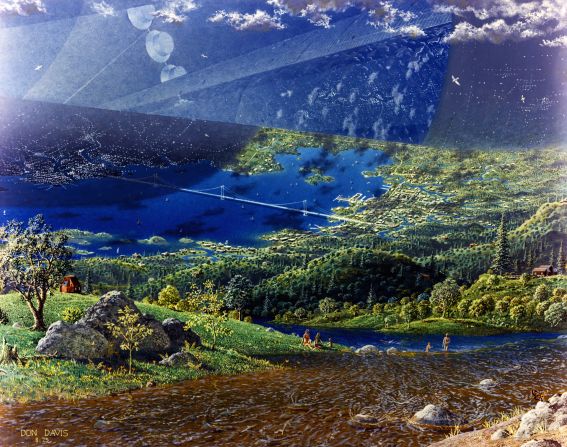

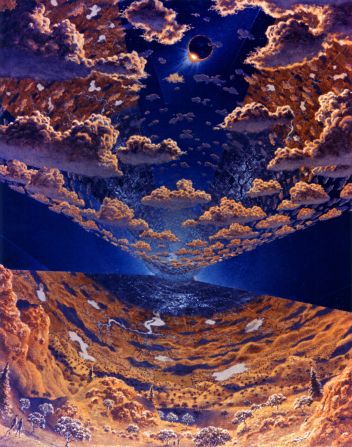

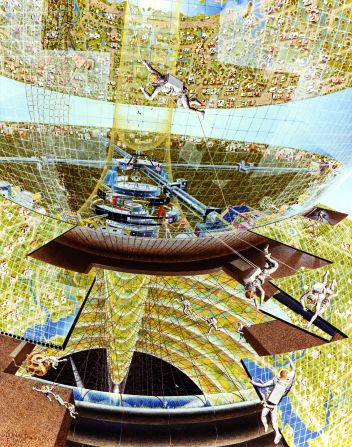

The river nearby shimmers in the light. You follow its course, your eyes gradually moving up, up, over your head and then down to the other side. Eventually the water meets in a perfect circle, back where you began. Everything is as it should be. You’re a resident of a Bernal Sphere, floating on the far side of the Moon – you’re used to the artificial gravity by now.

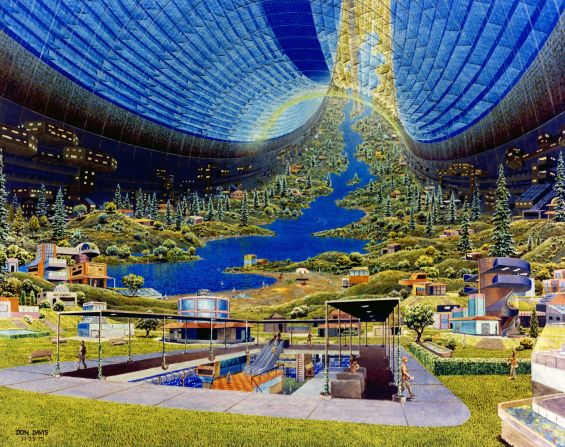

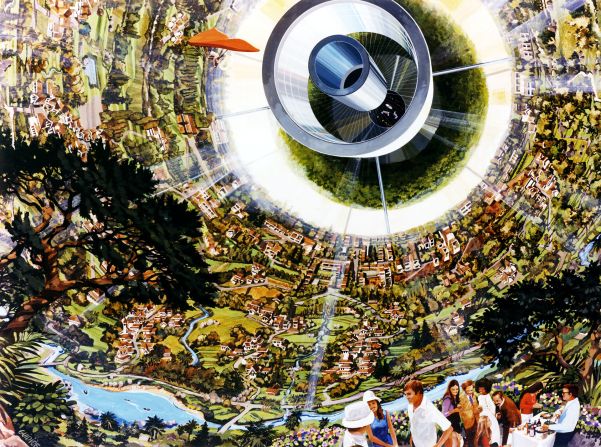

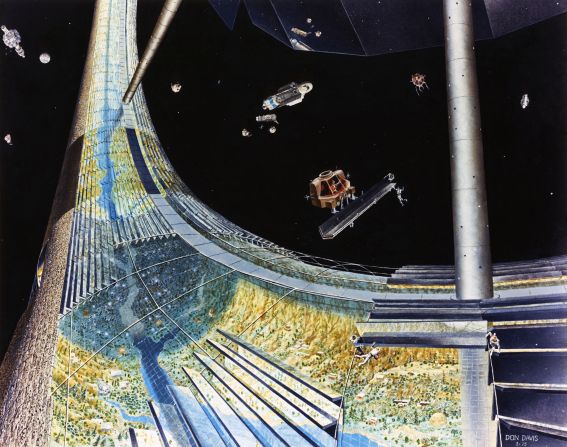

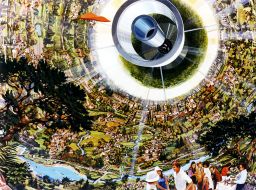

As retrofuturist artwork goes, few reach the outlandish heights of Rick Guidice and Don Davis, commissioned by NASA in 1975 to illustrate potential space colonies.

The designs sprang from the mind of a team at the NASA Ames Research Center, spearheaded by Gerard O’Neill, a Princeton professor given grants by the American space program to conduct a ten week study into off-world structures.

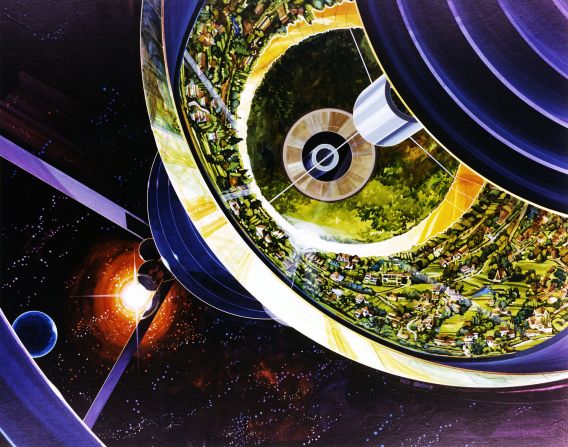

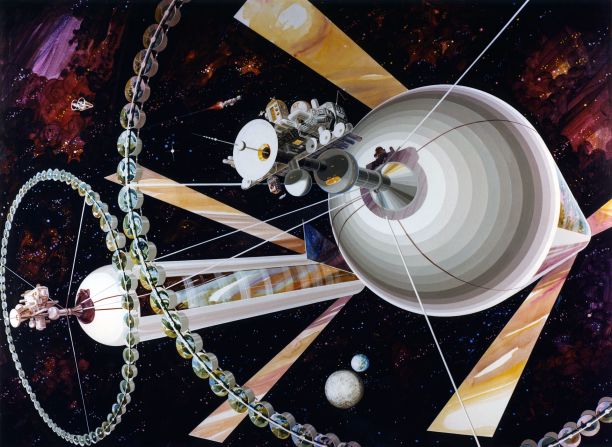

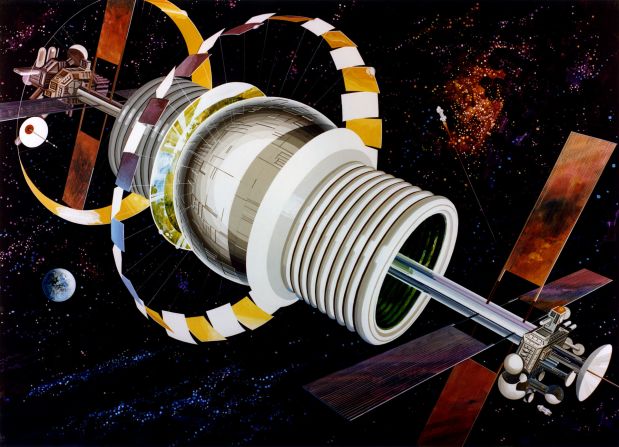

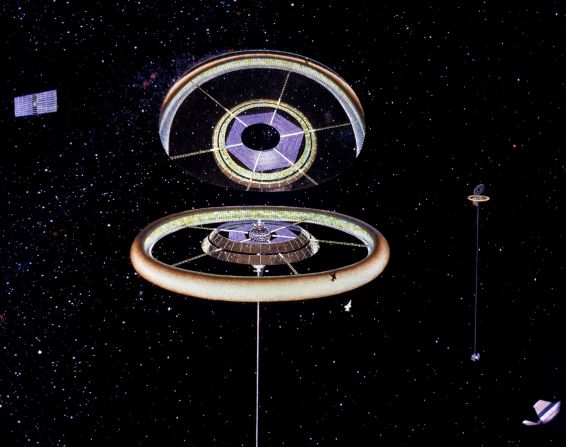

Working with architects, researchers, engineers and scientists in Mountain View, California, O’Neill assessed whether his ideas were feasible, eventually drawing up three concepts to present to NASA: the Bernal Sphere, the Toroidal Colony and the Cylindrical Colony.

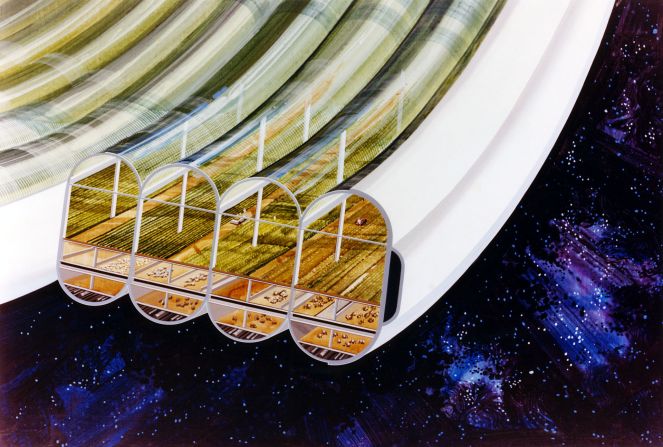

Each used centrifugal force to generate artificial gravity, reflected in their circular designs and vast solar arrays to power their rotation. Inside verdant landscapes offered comfortable living in Modernist homes.

Bauhaus structures popped up among lakes and forests; elsewhere whitewashed villas and terracotta patios brought Ionian charm to the cold vacuum of space.

The largest concept, the Cylindrical Colony, had the potential to hold a million people at a time. For all intents and purposes, they were like Earth – only turned inside out. O’Neill speculated that with the right technological developments, construction could begin as soon as 1990.

To view the designs with skepticism is to forget the milieu in which they were created: the last manned mission to the Moon was three years previous and Skylab, the United States’ first space station, was orbiting Earth. The space shuttle program, a giant leap which promised so much, was only around the corner.

The progress of mankind’s space programs must have been a crushing disappointment for O’Neill, who died in 1992. He aimed for lush vistas, but in truth we’ve only just learned how to cultivate lettuce. It will be a while before our space stations have room for combine harvesters – even longer, you’d expect, before you can hang glide inside of one.

Forty years on, O’Neill’s designs continue to intrigue, and have inspired numerous derivatives. Perhaps the most high profile was Cooper Station, a satellite seen in Christopher Nolan’s “Interstellar” – a compact version of the Cylinder Colony, later dubbed the “O’Neill Cylinder”.

It may yet be centuries before an object the size of O’Neill’s colonies is ever constructed in space. For now we’ll have to live with the images of what might have been – and what, just possibly, might still be to come.