Story highlights

A new study finds a Zika infection may cause more developmental problems than microcephaly

It appears there may be no date when a doctor can conclude that after a normal ultrasound all will be fine

Doctors discover another piece of the Zika puzzle, but it has left experts with more questions about this little understood disease.

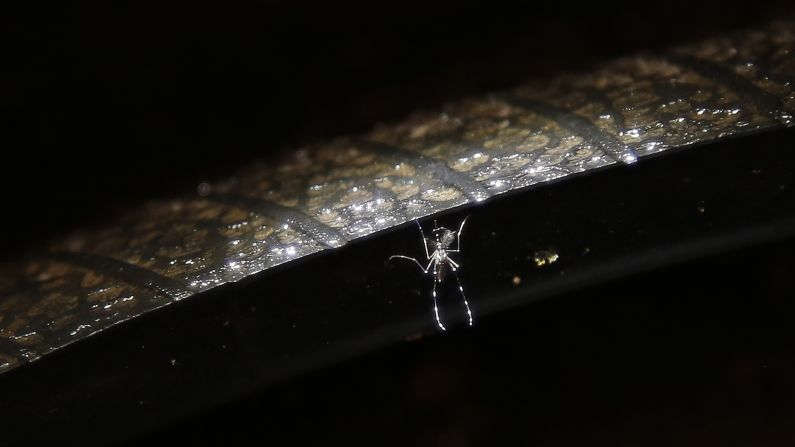

A study running in the latest online edition of the New England Journal of Medicine focuses on the case of a 33-year-old woman who went on vacation in November. She visited countries that are home to mosquitoes that carry the Zika virus: Mexico and Guatemala. She was 11 weeks pregnant at the time.

The woman remembered being bitten by mosquitoes in Guatemala. When she returned to her home in Washington, D.C., she didn’t feel well and went to the doctor. Her symptoms included a mild fever, muscle and eye pain and eventually she developed a rash. Tests showed that she was sick with a Zika infection.

When doctors did an ultrasound at 13, 16 and 17 weeks, the fetus looked fine and there was no sign of microcephaly, something some other infants that have been infected with the virus have had. But between the tests at 16 and 20 weeks, the doctors saw something strange.

The child’s head circumference fell from the 47th percentile to the 24th percentile. At 19 weeks the ultrasound showed the child’s brain was not developing normally. There were also problems with the lung, liver, spleen and muscle. With so many problems, the patient decided to end her pregnancy at 21 weeks.

This study only looks at one case, but it does explain what another study in the latest edition of the New England Journal of Medicine calls for: It gives further concrete evidence about what may happen in the case of a fetal Zika virus infection, and it shows that the problems may not be limited to microcephaly.

The case shows that the problems Zika may cause with a developing fetus may not show up on a normal ultrasound. The problems may also show up too late for a woman to make a decision about terminating her pregnancy depending on where she lives.

Other health experts have recently warned that there may be a “broad range of effects on a fetus beyond microcephaly” as Dr. Margret Chan, the director general of the World Health Organization, said at a news briefing last week.

At a news conference earlier in March, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, also talked about the challenges of detecting problems brought on by a Zika infection. He referenced individual reports where development problems haven’t shown up until 35 weeks into a woman’s pregnancy. With this being a problem that is not just in the first trimester “is really quite concerning,” he said.

An author of this latest study, Dr. Rita Driggers said one of the problems with this virus is that it appears there is no date when a doctor can conclude that after a normal ultrasound all will be fine. A regular doctor’s office would also be unlikely to have the equipment to see these finely detailed abnormalities.

Join the conversation

At a March 10 news conference, the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Dr. Tom Frieden said that he found the fact that the virus may harm a developing fetus in all three trimesters of pregnancy “striking.” He added, “I think what we’re saying basically is the more we learn about Zika in pregnancy, the more concerned we are.”