Editor’s Note: Robert Klitzman is a professor of psychiatry and director of the Masters of Bioethics Program at Columbia University. He is author of “The Ethics Police?: The Struggle to Make Human Research Safe.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

British researchers last week given OK to use gene editing on human embryos

Robert Klitzman: Tampering with nature undoubtedly has perils but also has big potential benefits

Every week, I get unsolicited email ads from airlines, Nigerian widows – and now biotech companies selling gene editing services. I usually just reflexively delete the biotech emails along with most of the others, giving them little thought. That was until last week, when British researchers made a momentous announcement: A British regulatory agency has given them permission to begin altering genes in human embryos.

We have entered a Brave New World.

So-called gene editing involves the use of technology, known as CRISPR-Cas 9, to alter the genes, or DNA, in our cells. One of the greatest technological discoveries in the past 50 years, if not longer, this powerful tool holds the promise of revolutionizing our lives and those of our descendants.

The technique, first discovered among bacteria trying to avoid viruses, lets us clip out bad genes in cells or insert better ones. Moving forward, the potential applications are enormous. If a mutation is destroying your cells, we could simply splice it out. As a result, countless patients could potentially be treated for horrific disease.

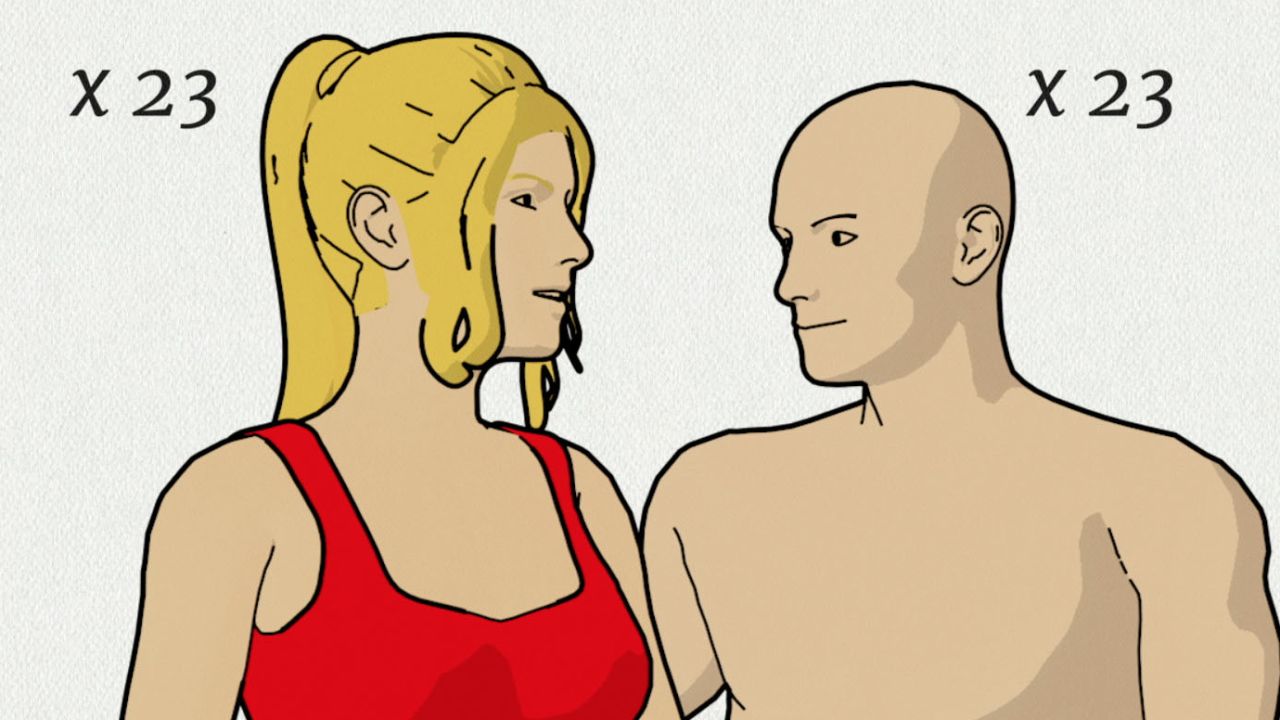

Ultimately, the technique could be used for altering genes either inside you – affecting only you – or in embryos that will mold your children and their descendants. In the future, parents may want to give their children certain genes for blond hair and blue eyes, added height or certain kinds of athletic prowess.

We may also eventually find genes that are strongly associated with perfect pitch, intelligence or homosexuality, for example, and parents may want to pick and choose among these as well. The possibility of altering or “enhancing” future humans may seem like science fiction but may soon be possible.

But there are risks. Certain genes may increase your odds of getting one disease but protect you against other ailments – if we impair such a gene, you may avoid the first disease but get another. For example, in mice, researchers blocked a gene that caused cancer, but the mice ended up aging prematurely. In addition, gene editing, at least in the near future, might also lead to mistakes such as parts of the wrong gene accidentally getting snipped.

Where do things currently stand?

Last year, Chinese researchers reported that they had tried to alter the genes in embryos but had encountered problems. International debate erupted: Should we allow this technology to proceed in humans? And if so, when?

Some critics argued that the research should be permanently banned. Many scientists, however, felt that the technology might be used in the future but not until the pros and cons were discussed in an international forum.

As a result, in December 2015, researchers from China, Britain, the United States and elsewhere held a summit in Washington to decide what to do.

They agreed to place certain limits on the technology, at least for now. They also decided that basic preclinical research, involving cells in petri dishes, should proceed as long as appropriate oversight and rules exist. Research on genes in our bodies that won’t be transmitted to future generations is also similarly permissible. DNA in human embryos could be changed but only if they are never implanted into a womb.

Researchers around the world were still trying to make sense of all this when suddenly, last week, the British researchers proclaimed that they were set to start their research. And while these embryos are not supposed to be implanted into wombs to become human beings, the fact that this research has now begun has thrust the issue back into the headlines.

Should we be worried?

Tampering with nature undoubtedly has perils, but having been very public about what they are planning, the UK researchers will be closely watched. It is therefore not so much what these researchers do, but what might happen in the future that we need to keep a close eye on. The reality is that all technologies are tools that people can use for good or bad. Nuclear research, for example, has given us relatively inexpensive electricity but also atomic bombs.

Similarly with CRISPR, careful oversight and transparency are crucial because “garage science” flourishes in many fields, as do researchers in countries with little oversight. If I am receiving emails selling these technological services, so too are countless others.

The other big question is whether U.S. scientists should also start such research in human embryos. On this, the answer seems to be that they probably will. Though Congress has decreed that federal funds cannot be used to destroy embryos, investigators can still use state or private funds.

We have now embarked on a long journey, and it is unclear what any of us will find. At times, we will be scared. But we should make sure we know and discuss each step that we take because it is unlikely we will ever completely be able to turn back.