Vital Signs is a monthly program bringing viewers health stories from around the world. This month’s show looks at water and health.

Story highlights

U.S. and beyond increasingly looking to reusing sewage water for drinking

Half the world population will face water scarcity by 2030

Reused water is completely healthy, but psychological barriers remain

Singapore produces large amounts of high-quality recycled water

A third successive year of California’s worst drought in a century has the Golden State’s reservoirs at record lows. Agriculture has been affected, hitting the local economy, while some small communities risk running out of water.

But business is booming in California’s Orange County Water District (OCWD), through a pioneering wastewater treatment facility that recycles used water – or sewage – and returns it to the drinking supply. The plant is expanding production from 70 to 100 million gallons per day, enough for 850,000 people, around one-third of the county population. As the OWCD output is mixed with the main groundwater supply it reaches over 70% of residents.

Global problem

The facility is among the oldest and largest of its type in the world, and could represent a model solution for a global problem. The U.N. warns that half the world population will face water scarcity by 2030, accelerated by climate change and population growth. Shortages on such a scale would threaten food production, as well as a health crisis through increased exposure to unsanitary water, which already kills millions each year through waterborne diseases such as cholera and diarrhea.

But the introduction of reuse systems has been difficult, with a high degree of public skepticism. Orange County began recycling water for non-potable use in the 1970s, but only began contributing to the drinking supply in 2008, combined with a comprehensive PR and education campaign to allay public fears.

Operators now feel the system is well established and ready to scale up. “It’s a watershed moment right now, we’re seeing widespread acceptance of these technologies,” OCWD General Manager Mike Markus said. “As the shortages become more extreme and water supplies are cut, it has raised awareness that we need to find alternative resources.”

The process works by re-routing a proportion of the 1.3 billion gallons of waste water generated in Southern California each day into a three-step treatment. The first is microfiltration of the treated waste water to remove solids, oils and bacteria, before the resulting liquid goes through reverse osmosis, pushing it through a fine plastic membrane that filters out viruses and pharmaceuticals. The water is then treated with UV light to remove any remaining organic compounds, before joining the main groundwater supply, which must pass strict quality controls to meet legal standards, and distribution to households.

Read this: Machine makes drinking water from thin air

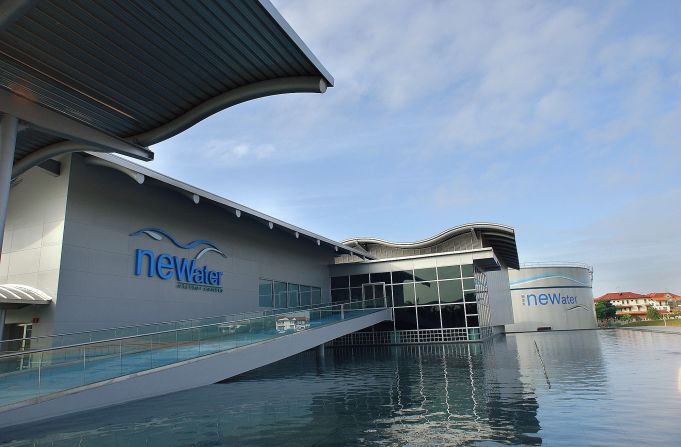

The OCWD says the water exceeds all state and federal drinking water standards. Safety has also been established in pioneering projects around the world. Water-insecure Singapore, previously reliant on imports, now delivers 30% of its needs through the NEWater reclamation facility. Although only a small amount is added to its reservoirs, the output surpasses WHO standards for potable use to the extent that a high proportion is directed for industrial uses requiring ultra-clean water.

One of the world’s earliest schemes, in Windhoek, Namibia, has been in operation since 1968 and has tackled both shortage and water-borne diseases. Over half of the Sub Saharan African population faces water insecurity, and the greatest health risk, diarrhea, kills over a million people each year in the region. But research showed that in the 1970s disease occurred at lower rates for people supplied by the Windhoek plant than through conventional treated sources.

“Standards are stricter because of the novelty of the technology and process,” says Benedito Braga, President of the World Water Council. “The quality from sewage is very good, as good or better than the tap water in any city in the developed world.”

The message is now being heeded and the model is spreading. California has put $1 billion into funding recycling for potable use ($800 million of that in low-interest loans), with new initiatives launched in Los Angeles, San Francisco and San Diego.

Texas, parts of which are also severely affected by drought, aims to generate 10% of all new supplies through reclaimed water by 2060. A facility in Big Spring has introduced the first “Direct Potable Reuse” scheme in the United States by sending recycled water to the final treatment plant without passing it through groundwater reserves.

Dealing with disgust

In each case, public relations are key, as recycled water schemes have been historically shot down by public disgust at the concept. This was most vividly shown in the Australian city of Toowoomba in 2006 when local activists represented by the group “Citizens against drinking sewage” defeated plans to introduce reclaimed sources, citing health risks and emotive factors.

But Australia also shows the extent to which attitudes have changed. After a three-year public trial, the city of Perth will receive up to 20% of its drinking water from reclaimed sources in coming decades, with a reported 76% public support. A network of similar programs is being established across the country, according to the Australian Water Recycling Center of Excellence.

Psychologists say the aversion is deeply held and difficult – but not impossible – to overcome. “The disgust comes from intuitive concepts of contagion,” says Dr. Carol Nemeroff of the University of South Maine, who has studied reactions to reclaimed water. “It is magical in nature, the same type of thinking that underlines voodoo practices.”

“One of the best ways to get past it is perceptual cues – if you can see sparkling fresh, clear water, and taste it that helps to overcome the concept … the contagion type thinking decreases with familiarity,” says Nemeroff, adding that necessity can also be a key driver. “If you’re desperate you’ll override anything for survival.”

Energy and cost

In Orange County and other facilities, mixing the output with groundwater is a largely unnecessary, confidence-building measure to allay public fears. But as awareness improves, operators hope to move from indirect to direct potable reuse, which would bring down energy use and costs, while avoiding the counter-intuitive step of re-contaminating purified water.

“The main cost is energy and that is coming down all the time,” says Mike Markus. “Improvements in membrane technology allow us to use less pressure to do the same thing.” The energy cost of reverse osmosis has come down by 75% since the 1970s, he says, while emerging technologies such as Aquaporin may reduce it further. Even now, the cost is favorable compared with desalination or imported water in California.

Markus hopes such advances will allow for the creation of portable modular units that can be cheaply transported to the areas of the world with the greatest need.

Campaign group Water Reuse does much of its work in education outreach, through messages such as the “Downstream” concept, that all water is ultimately recycled. “It’s the same water now as when dinosaurs walked the earth,” says executive director Melissa Meeker. “It’s about understanding the water cycle and how we fit into it. Once people think about it, they become more open-minded.”

If costs continue to fall and public acceptance continues to grow, waste water can become a major defense against the projected scarcities of this century. The World Water Council projects that recycled sewage will be a normalized source of drinking water in cities around the world within 30 years, and much of the infrastructure and technology is already in place. It’s up to us now to get used to it.