Editor’s Note: Gareth Evans is a school teacher in Cape Town, South Africa. In 1983, he was nine years old when he attended Newlands Cricket Ground for the “rebel tour” cricket match against the West Indies at a time where there was a sporting boycott against the apartheid state. After watching CNN’s award-winning documentary, “Branded a rebel,” Evans recalled his experiences.

Story highlights

Sporting ban to campaign against apartheid in South Africa introduced in 1977

"Rebel tours" were highly controversial, unofficial, international matches

Team of West Indian cricket players visited South Africa in 1983

They were shunned by society on their return home to the Caribbean

My mom was always sports mad – my dad not so much.

But both my parents understood the importance of significant events, so when opportunity knocked, my parents opened up all doors for me.

I grew up knowing full well that my country wasn’t allowed to participate in international sports following the sporting boycott of 1977 which had been placed on South Africa in a protest against apartheid – a system of racial segregation enforced by the ruling white minority.

So when the South African rugby team toured New Zealand in 1981, my parents made sure that I was awoken at 04:30 to watch all three Test matches.

I got to snuggle between my parents – and a first – they put the television in their bedroom.

It was the “flour bomb” Test – where a light aircraft flew over Auckland’s Eden Park before and during the match, dropping flour bombs, smoke bombs and anti-apartheid leaflets – where I began to realize that other countries didn’t like us.

I didn’t understand why at the time, and it hurt a little. Later that day, I’ll never forget my parents telling me that it could be a long time before I witnessed something like this again.

I was six at the time. They were right; I would next see these two teams play as a 17-year-old.

First trip

My first trip to Cape Town’s Newlands Cricket Ground was to watch Western Province play a domestic match. It must have been my mom’s first trip too, because I distinctly remember entering the ground and ending up sitting on the grass embankment, which was reserved for colored people.

Confused, we sat down. A kind couple offered us some fruit, so we stayed. I was blissfully unaware of how significant this possibly was.

We returned a couple of years later to watch my first “Test” match: South Africa vs. the West Indies. This time we were seated in the correct place, in the Oaks Enclosure, which ironically these days is a grass embankment.

Read: The man who took on South Africa’s apartheid regime

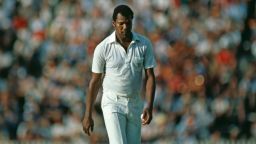

I remember the hype and the excitement about this special day. I had seen the Windies in their warmup game against Western Province and I knew that they were something special.

They had vicious fast bowlers and flamboyant batsmen. We got there early, along with thousands of others, just to watch the warmups. The excitement was tangible.

What is apartheid?

What is apartheid?

I don’t remember much about the games – I remember more about the players. They were heroes to us.

Perhaps there was some curiosity too, something about the islanders from far, far away on our shores. We used to follow them around the boundaries of the ground, hunting their prized autographs. And their accents – just too cool.

Didn’t see color

I know I didn’t see the color. I don’t think most kids did – they were just cricketers. At the end of play we would run on the field to try to touch them and grab one more autograph.

Somewhere there is footage of me congratulating Sylvester Clarke by patting his back. I remember telling all my friends that I had touched the great bowler.

While I had forgotten about it, listening to Franklyn Stephenson speak reminded me of the time we were trying to get him to drink from some kid’s Coke. He obliged and we all simply went crazy.

I realize the significance of that event now. Imagine a black guy drinking from the same can? Perhaps our parents would have flipped out, but this wasn’t about color to us.

Other memories include how obliging and friendly they were. Happy to give autographs and happy to interact positively with the huge crowds.

Branded a rebel

It was with incredible interest and fascination that I watched “Branded a rebel” – a CNN World Sport documentary which first screened last year.

It gave me greater insight into the players, the tour, West Indies cricket and indeed my home country. And while “Branded a rebel” is an appropriate title for the program, it could have just as easily been titled “Branded Heroes.”

That’s what they were to us white South Africans, and I think deep down the Windies players felt that too. It’s all about what side of the line you were sitting, I guess.

On their return home, the West Indian players were shunned by society and some were forced to move abroad to make a living.

The poverty and other such ills which befell some of their players really tugged at all of my emotions. I started thinking what we as South Africans could have done for them.

Could we have done more? Did we look after them well enough after the fact? It’s a difficult one. These men didn’t deserve it, no matter what choices they made. Society can be cruel.

Strangled by hatred

It eats me up to think what those players endured upon their return. They were strangled by such hatred in their home countries, and yet I wish they somehow knew what they had done for young cricket fans like me.

I got to see “real” international cricket played at the “highest” level. I got to meet new cricketing greats.

I got to bowl like Clarke, Collis King and Colin Croft. I got to emulate David Murray’s great wicketkeeping skills on Clifton beach, field like Alvin Kallicharan and admire the patience and masterful batting of the great Lawrence Rowe.

And something else – they taught us not to take ourselves too seriously by showing how much one can enjoy themselves on the sports field. Their smiles, I’ll never forget their smiles.

Read: Sporting mercenaries or crusaders for a cause?

Each of their names is entrenched in my memory, and of all of those who saw the matches. They became part of my upbringing and that of thousands of South African fans.

What I didn’t understand at the time, was what it took for those men to actually land on our shores (money aside).

They must have been scared – really scared. I know I would have been. In the interview with Clive Lloyd, longtime captain of the official West Indies team that dominated world cricket for two decades, he said no amount of money would have made him support a racist regime.

I would go as far as to say no amount of money would have put my fears at ease to travel to South Africa.

Courage

It’s not for me to judge, but those men were courageous. In their cricket and in their collective decisions, and I respect that.

A few years later, I did wonder how the black West Indian players got to travel using “white” transport and stay in “white” areas. I remember asking my mom how that worked. She didn’t know, but you could see that my political curiosity was growing.

I was disappointed that more players didn’t take up the opportunity of being interviewed for the documentary. I was intrigued by Stephenson, King and Murray’s thoughts, motives and reflective answers. There seemed no real regret, which was fascinating and pleasing for some reason. As for those who declined an interview, their wounds obviously cut deep.

Stephenson was just how I remember him. Boisterous, bubbly and always looking on the bright side of life. We got to know him well here, as he returned to play for the Orange Free State.

The fact that he still has all his memorabilia means that the tour meant something to him, and that he feels part of change and change of attitudes in South Africa.

I don’t know if they changed us as a society but I’d like to thing so, even if it was an indescribably fractured and dysfunctional society.

And by this I mean that white South Africa packed out every cricket ground to watch black West Indies, went home and made sure that “The Cosby Show” was the most watched program on television – and yet black people were pretty much denied and excluded from everything.

Heart bleeds

“Branded a rebel” showed balanced reporting. I like the fact that you saw the tour from a South African perspective as well.

Great players like Graeme Pollock, Barry Richards and Clive Rice also effectively served life bans for being, well, South African, and the program understood that.

I know that, fundamentally, the tour was morally corrupt, but for an innocent nine-year-old devoid of political allegiances and beliefs, it was simply a chance to see the world’s best cricketers entertaining us on the world’s most beautiful stage.

Ultimately, I’d also like to believe that South African cricketers and administrators were trying to show the government the way forward, and that unity through sport was possible.