Editor’s Note: Ulf Gartzke teaches at Georgetown University’s BMW Center for German and European Studies and is the managing partner of business advisory firm Spitzberg Partners in New York. He formerly headed the Washington office of the Hanns-Seidel-Foundation, the political think tank and foundation of Germany’s ruling center-right CSU party, and worked at the World Economic Forum in Geneva.

Story highlights

Angela Merkel's parties scored big victories in Sunday's Bundestag elections

Ulf Gartzke: Merkel's calm, unpretentious approach and strong economy help her cause

He says Merkel has walked fine line, propping up Euro, without losing popularity at home

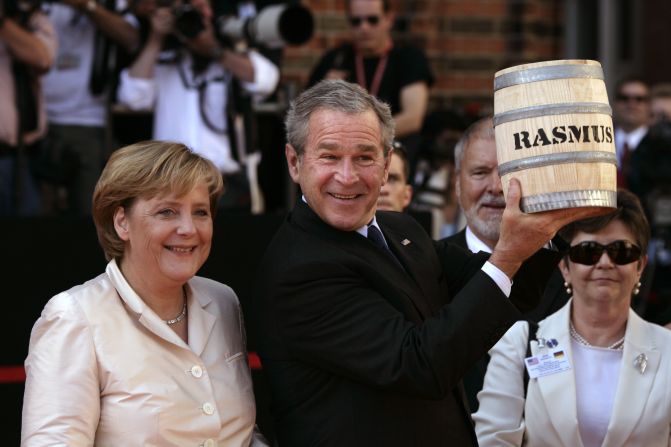

Angela Merkel has come a long way. Once dismissed by hard-core conservative critics as “the divorced, childless, Protestant woman from former East Germany”, the German chancellor’s landslide victory in Sunday’s Bundestag elections has reinforced her position as the uncontested political leader in Germany and the rest of Europe.

For a few hours Sunday night, Merkel’s center-right CDU/CSU parties seemed even within striking distance of an absolute majority of seats, a feat only West German CDU “Uber-Chancellor” Konrad Adenauer achieved in 1957.

Under the rules of Germany’s complex electoral system, the Conservatives received 41.5% of the vote but 49.3% of the seats (five members short of an absolute majority in the 630-strong Bundestag).

Above all, Sunday’s elections have confirmed that a vast majority of Germans are supportive of Berlin’s handling of the European sovereign debt crisis – and specifically, Germany providing financial backing in return for structural and fiscal reforms in crisis-hit Eurozone countries.

In contrast to other major Western leaders who are struggling at home, Merkel’s calm, disciplined and unpretentious approach to governing resonates with many German voters who feel confident she will protect them against the uncertainties and crises abroad. By firmly occupying the German political center (“Die Mitte”) Merkel has successfully marginalized the SPD/Green opposition parties (she even decided to phase out nuclear power).

Add to that Germany’s strong economic performance and low unemployment figures and you have the secret recipe behind the success of Angela Merkel.

Even CDU/CSU party insiders were surprised at the magnitude of her election victory (an increase of 7.7 percentage points compared to 2009), especially since successive bail-out packages, the European Central Bank’s aggressive bond buying, as well as the European Stability Mechanism fund have increased Germany’s Eurozone liability exposure to hundreds of billions of Euros.

In late August, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble, a close Merkel ally, caused some political consternation within the center-right camp when he alluded to the possibility that Germany may need to sign off on a third bailout package for Greece.

Schaeuble’s comments, while politically risky, seemed to confirm what many economists have suspected all along: namely that the Greek drama is not over, that Athens will ultimately need significant debt forgiveness to regain its footing, and that there are other Eurozone countries – ranging from Portugal to Ireland, Slovenia and Cyprus – that will soon be asking for more (German) money.

Yet Sunday, even the resurgent anti-Euro “Alternative for Germany,” or AFD, party missed the 5% threshold needed to enter parliament, thus providing relief among international investors that Berlin is not beginning to pull the financial plug on the rest of Europe any time soon.

Quite to the contrary, since the demoralized pro-business FDP party failed to enter the Bundestag for the first time since 1949. Merkel will now have to find a new coalition partner and could theoretically either join forces with the Social Democrats, known as the SPD, or the Greens.

Both opposition parties have frequently criticized the outgoing center-right government for putting too much emphasis on austerity rather than on growth measures to kick-start the fledgling Eurozone economies.

The SPD and Greens are also strong supporters of the controversial Eurobonds that have been categorically rejected by Merkel for fear they would remove all incentives for individual European countries to get their fiscal and economic houses in order.

While Merkel is going to stand firm in her opposition to Eurobonds a new German government with either the Social Democrats or the Greens on board would be more open to making concessions on the planned European banking union, especially regarding the proposed single resolution authority mechanism to be placed within the European Central Bank.

Pretty much everything will depend on the internal horse-trading during the upcoming coalition talks between CDU/CSU and SPD and Greens, respectively.

Ultimately, most political observers agree that Merkel’s next government (and her last since she has already said she won’t run again in 2017) will probably be a relaunch of the Grand Coalition with the SPD that she led during 2005-2009.

While the SPD is rather reluctant to enter into such a deal (after all, it scored its worst post-war result in the 2009 elections), the party knows full well that a Grand Coalition is the preferred option for a majority of German voters. In theory, getting the SPD on board should also help Merkel break the political gridlock that has gripped German politics since the opposition SPD, Green and Left parties retain control of Germany’s upper chamber (the Bundesrat), which nowadays needs to approve about half of all German laws.

From an American perspective, the re-election of Angela Merkel is definitely good news and promises a certain stability and continuity in an otherwise rather weak and fluid European political leadership landscape.

In principle, the Chancellor’s commitment to free trade should also provide valuable political cover for the planned U.S.-EU Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership at a time when protectionist sentiments are running high, especially in France and the Southern European countries.

That being said, as evidenced by the Syria crisis, a future Merkel administration that includes either the SPD or the Greens would probably be even more reluctant to use military force abroad than the outgoing center-right coalition government.

Merkel’s victory in the 2013 Bundestag elections is of historic proportions. Political commentators are already speaking about “the era of Merkel” and note that the woman who spent well over half of her adult life in East Germany is even beginning to eclipse her one-time mentor Chancellor Helmut Kohl, the father of Germany’s reunification in 1990. The next four years will determine whether Merkel’s leadership and handling of the Eurozone crisis will keep the European project together.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Ulf Gartzke.