Story highlights

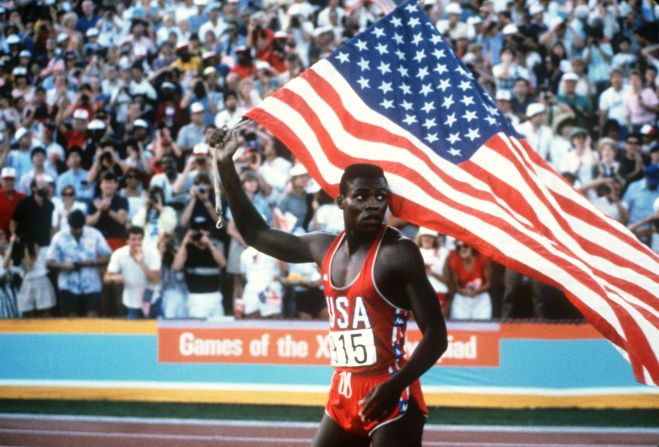

CNN talks to disgraced former 100 meter sprinter Ben Johnson

He smashed the world record at Seoul 1988, but failed a drugs test

The race has been dubbed the dirtiest in history

Six of the eight athletes in Seoul later connected to drugs

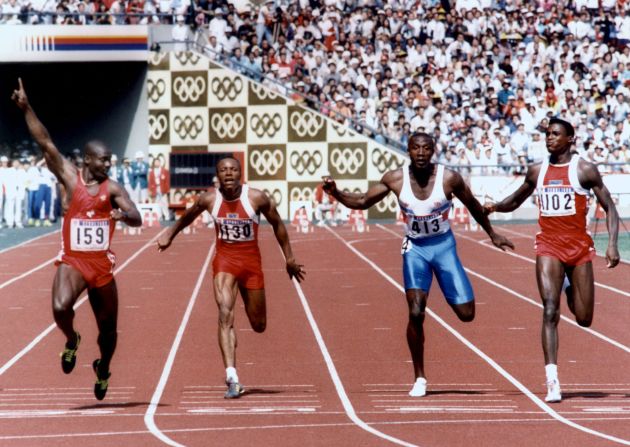

Ben Johnson was the last man to settle into his blocks at the Seoul Olympic Stadium.

It was September 24, 1988, a heartbeat before the start of the 100 meters final and what was to become the most infamous sporting moment in Olympic history.

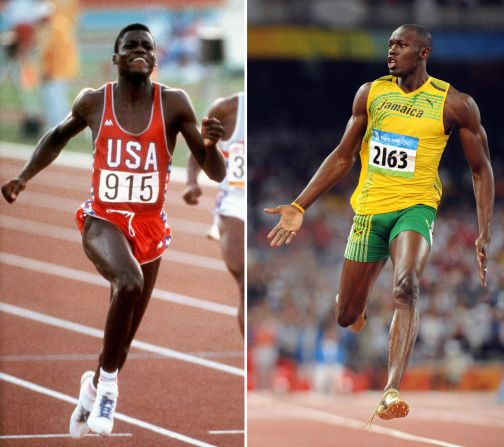

Johnson, like the rest of an-all star field that included then Olympic champion and fierce rival Carl Lewis, former world record holder Calvin Smith and future gold medalist Linford Christie, paced back and forth like caged panthers seeking the psychological advantage of settling last.

The field stretched, hopped and feinted as they pretended not to look at each other. Johnson merely stared straight ahead, unblinking. Inevitably it was he who won the first battle.

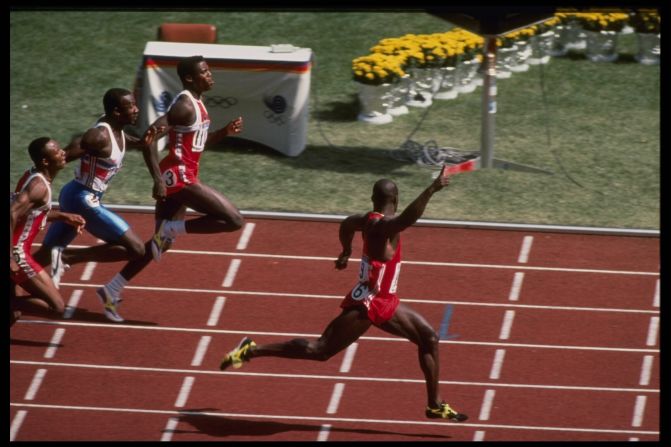

The gun fired and the Canadian leaped – literally leaped – from his starting position into a lead he would never lose.

Just 9.79 seconds later he had smashed the world record in a display of power and awe never before seen in track and field, against the greatest field of sprinters ever collected.

“Nobody,” Johnson recalls in an interview with CNN, laughing in deep, long chugs, “nobody could touch my start.”

What happened next has been seared into the collective memory of the Olympics ever since.

Opinion: What changed the Olympics forever

The image of a medal ceremony, more than 24 hours later where Carl Lewis still can’t come to terms with where Johnson had found his extra power; the incredulity on the faces of the journalists present; the press conference afterward where a triumphant Johnson eulogized.

“I’d like to say my name is Benjamin Sinclair Johnson Jr, and this world record will last 50 years, maybe 100,” he had told the room. Later he said: “A gold medal – that’s something no one can take away from you.”

But they could take it away from him.

And they did.

Just 24 hours later Johnson had failed a drugs test when traces of the banned steroid stanozolol were found in his urine. And after delegation arrived at his room. Johnson handed the medal back to the IOC, much to the consternation of his mother. One of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) officials present described the scene as like a “wake.”

“It is something that I can’t watch because of what happened to me, you know?” says Johnson now of his emotions ahead of the 100m race in London, which will feature Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt and will once again be most watched event at the games.

“It is a sad note how they left me, wringing me out. I don’t really watch it. I just move on with my life.”

The race was just one moment in a two-decade-long story that began with Johnson as a Jamaican immigrant in Canada. His rise to prominence on the track for his newly adopted country would end with a descent into sport drug use and finally disgrace.

Yet he wouldn’t be the only one. Doping was so prevalent in the sport that six of the eight finalists that lined up on that September day in Seoul would fail drugs tests themselves or implicated in their use during their careers, including Lewis and Christie. As the writer Richard Moore describes in his new book on the 100m final in Seoul, it was the “Dirtiest Race in History.”

The fight against drugs

“There was a huge problem with the fight against drugs,” says Moore of attitudes against doping before the Seoul Olympics.

“Clearly it wasn’t in the sport’s interest to have the exposure for cheats so it was very much the fox guarding the hen house…It was a surprise to uncover how primitive that fight was back in those days. (Then head of the IOC Juan Antonio) Samaranch couldn’t care one way or the other. He was ambivalent on the whole subject.

“There were one or two individuals in the IOC who were keen to fight it. But it was very limited.”

Johnson began his career at a time of rudimentary doping controls that Moore dubs “the wild west.” Born in Jamaica in 1961 into a working-class family in Falmouth, Johnson moved to Canada with his mother aged 15.

He found solace on the track and soon found his calling in sprinting. It was in Toronto’s Scarborough district that Johnson would meet the man who would change his life forever: the trainer Charlie Francis.

South Sudan marathoner is an Olympian without a country

Francis was a former Canadian national sprinter who took Johnson under his wing and began a course of steroids for him in 1981 believing that it was the only way to compete in a sport riddled with drug use.

“The question is, why would you not if you know your competitors are getting away with it?” asks Moore.

“As Charlie Francis said: ‘You can set your blocks up a meter behind the starting line or you could be equal.’ And I think he was right. If you speak to anyone from that era they said he was right.”

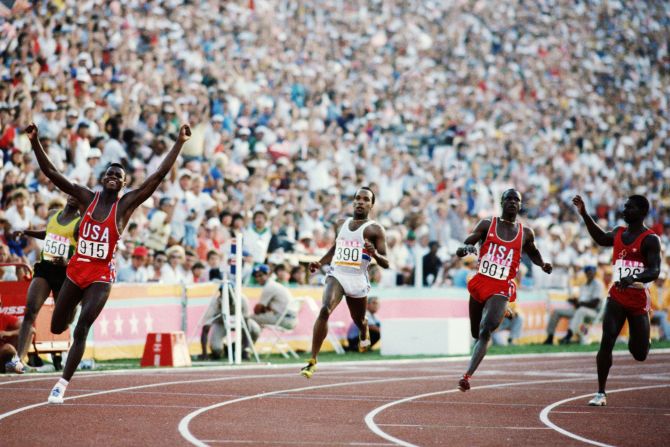

Francis’ techniques helped Johnson find a new level. As Moore points out, Johnson “went from a scrawny guy to a muscle-bound freak” within a few years. He won bronze in the 100m final at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, as well as bronze in the 4x100m relay. But he was still way off the pace of Lewis, the golden boy of American track and field whose performances defined the L.A. Games.

A loaded field?

In the period between Los Angeles and Seoul, Johnson’s work on and off the track was bearing fruit. He rose to be Canada’s best sprinter and began to challenge Lewis, with whom he enjoyed a cantankerous rivalry. But for Johnson it was clear that he was not the only sprinter who was doping.

“It was something that I saw myself; people’s profiles were changing very, very fast,” Johnson says of how he viewed other athletes on the track at that time.

“Usually you don’t ask what they were taking because you mind your own business and concentrate on yourself.”

A harbinger of the Seoul Olympic scandal was the 1987 World Championships in Rome where, according to Moore, the catacombs that surrounded the practice arena next to the Colosseum were “a drugs den, full of needles and syringes.” By now Johnson had established himself as world number one and set a new world record there. It was the fifth time in a row he had beaten Lewis.

The dirtiest race in history

The scene was set for the greatest 100m final of all time at Seoul. In many respects it still is, despite the taint of drugs. Only two of the eight runners remained clean throughout their careers: American sprinter Calvin Smith and the Brazilian Robson da Silva. But the race, even today, has an explosive power that makes it impossible to ignore, with four of the field breaking the 10-second barrier. Johnson, perhaps unsurprisingly, believes it is still the greatest race of all time.

“Regardless what the IOC think, it’s definitely the best race ever run even though I hadn’t run my best race yet and you can tell that I have more fuel left in the tank,” he explains before claiming that drugs don’t actually make you run faster.

“You only cheat if no one else was not doing it. I was aware of what other people were doing in the field. I just did it better than anyone else. It doesn’t make you a fast runner … It was my training regime that was better than the rest of the world. My training was tailored for Ben Johnson and my coach was a genius. Now the whole world is using my program.”

The Jamaica-born Johnson

The rest of the world sees Johnson’s legacy slightly differently. He was sent back in disgrace to an angry Canada that had embraced its adopted son only to feel humiliated in the eyes of the world. Johnson left for Seoul as a Canadian and returned Jamaica-born.

“I think it was racist the way it was spoken back then. It kind of hurts a little bit,” he says of his return.

“They didn’t give me the benefit of the doubt. They didn’t protect me. If this was any other country in the world the government would have come in and protected the athletes.”

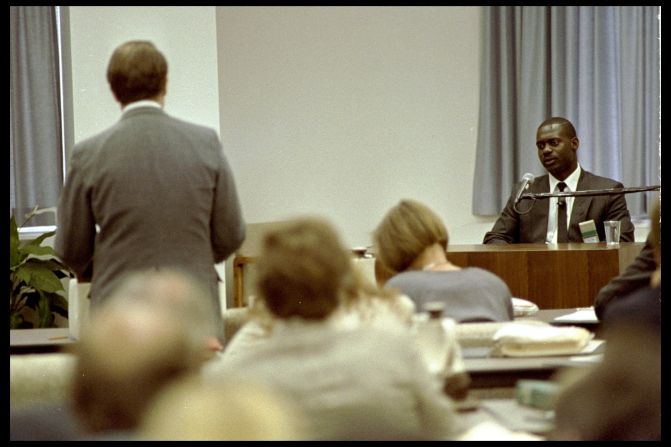

Instead Johnson and his coach were called to the Dubin Inquiry, set up by the Canadian government to uncover the extent of drug use in sport. After initially denying he had taken steroids, Johnson admitted doping there for the first time. But it was the testimony of Francis, who died in 2010, that lifted the lid of the extent and scope of drug use in sport.

Unbelievably little was learned from the scandal.

“Absolutely nothing changed after 1988, nothing,” says Moore. It would be, after all, a full 12 years before the World Anti Doping Agency (WADA) would be formed. What was the reason for the wait?

“They (the IOC) were very blasé about it. It wasn’t a fight they wanted. It wasn’t exactly great news for athletics or the Olympics, was it?” says Moore.

It wasn’t until the Festina doping scandal broke at the 1998 Tour de France that things started to change, but only after IOC president Samaranch had made controversial comments to Spanish newspaper El Mundo that the number of banned drugs be slashed.

“He betrayed what he really thought and undermined their anti-doping efforts. They had to do something dramatic and set up WADA … If those words hadn’t been reported it might not have happened. That’s what (former head of WADA) Dick Pound thinks.”

A life less ordinary

But it was all too late for Johnson. A comeback was stillborn after he again failed a drugs test in 1993 and was banned for life. He spent the next few years drifting from job to job, at one point even working as a personal trainer in Libya for Colonel Gaddafi’s son Saadi, who had pretensions of becoming a professional soccer player.

Today Johnson appears to have found a home and some stability. He now coaches aspiring soccer stars at the Genova International Soccer School in Italy. He still burns with what he sees as the unfairness of his treatment by the IOC, making conspiratorial claims that he was sacrificed while others were “protected who were taking the same thing.”

Implausibly his latest theory is that he was sacrificed because of a dispute between rival shoe sponsors. Although in his book “Speed Trap” the late Francis – who had been painfully honest about how he gave drugs to his athletes – claimed there was no way Johnson could have failed a drugs test for stanozolol. The reason? He’d been giving him a different steroid altogether.

Johnson will always be a pariah, synonymous with those blistering few seconds when he flew too close to the sun before crashing back to earth. Yet the experience hasn’t diminished his belief that he still deserves a place among the pantheon of greats.

“The runners today can’t compare to what I was running 25 years ago,” he claims, citing better, harder tracks more suited to the modern generation of sprinters. He believes he would break the 9.5 second barrier if running today.

“No sprinter today could bench-press 395 pounds. In 1987 to ’88, I won 25 finals against the best sprinters and that never happened today. Unbeatable.”

Even if today’s sprinters couldn’t possibly get away with taking drugs?

“I mean the doctors back then and now there’s no difference. If you know what you are doing, these athletes can bypass the detecting at the front gate,” he again claims conspiratorially.

“I know people are taking a lot of different drugs at the same time.”

He again breaks into his deep, chugging laugh for the second, and last, time.

“And they’re still running slower than me.”