Story highlights

At Mexico 1968, Australian sprinter Peter Norman won silver in the 200 meters

He was the third man on the podium during the infamous Black Power salute

Norman was shunned on his return to Australia for joining the protest

A film sheds new light on his role in one of sport's most iconic moments

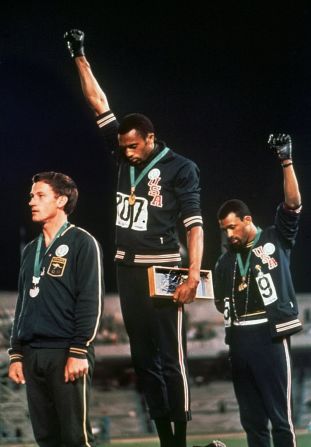

It is perhaps the most iconic sports photograph ever taken.

Captured at the medal ceremony for the men’s 200 meters at the 1968 Mexico Olympics, U.S. sprinter Tommie Smith stands defiantly, head bowed, his black-gloved fist thrust into the thin air.

Behind him fellow American John Carlos joins with his own Black Power salute, an act of defiance aimed at highlighting the segregation and racism burning back in their homeland.

It was an act that scandalized the Olympics. Smith and Carlos were sent home in disgrace and banned from the Olympics for life. But they were treated as returning heroes by the black community for sacrificing their personal glory for the cause. History, too, has been kind to them.

Yet few know that the man standing in front of both of them, the Australian sprinter Peter Norman who shocked everyone by powering past Carlos and winning the silver medal, played his own, crucial role in sporting history.

On his left breast he wore a small badge that read: “Olympic Project for Human Rights” – an organization set up a year previously opposed to racism in sport. But while Smith and Carlos are now feted as human rights pioneers, the badge was enough to effectively end Norman’s career. He returned home to Australia a pariah, suffering unofficial sanction and ridicule as the Black Power salute’s forgotten man. He never ran in the Olympics again.

“As soon as he got home he was hated,” explains his nephew Matthew Norman, who has directed a new film – “Salute!” – about Peter’s life before and after the 1968 Olympics.

“A lot of people in America didn’t realize that Peter had a much bigger role to play. He was fifth (fastest) in the world, and his run is still a Commonwealth record today. And yet he didn’t go to Munich (1972 Olympics) because he played up. He would have won a gold.

“He suffered to the day he died.”

An obscure pick

Peter Norman grew up in a working-class district of Melbourne. As a youngster he couldn’t afford the kit to play Australian Rules Football, his favorite sport. But his father managed to borrow a secondhand pair of running spikes, and his talent for sprinting was quickly recognized. Yet Norman was still an obscure pick when the 28-year-old arrived in the high altitude of Mexico City. It was the first time he had run on an Olympic standard track, and he thrived in the thin air.

“I could feel my knees bouncing around my chin,” Norman said in “Salute!”

“It lengthened my stride by about 4 inches!”

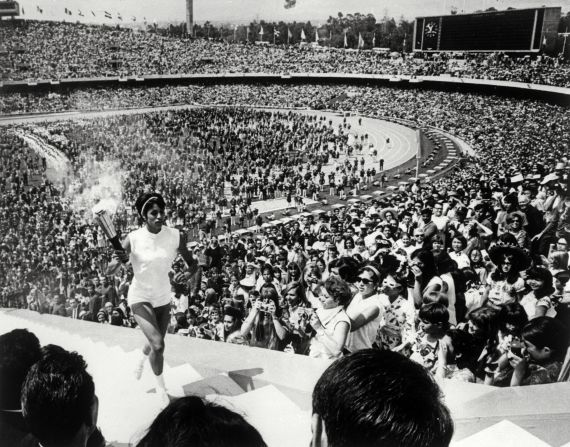

It was events off the track that had dominated the lead-up to the 1968 Olympics. In the U.S., the civil rights movement fought running battles with the police and army across America against segregation and racism. Both Martin Luther King Junior and Robert Kennedy had been assassinated and the Vietnam War was raging.

Meanwhile, in Mexico, hundreds of protesting students were massacred in the run-up to the Games. The regime covered up their deaths as the athletes arrived.

Australia too, was in the midst of racial strife. The country’s “White Australia” policy had provoked protests of its own. It put heavy restrictions on non-white immigration – and a raft of prejudicial laws against its indigenous aboriginal population, including a policy of taking Aboriginal children from their birth parents and handing them to white couples for adoption, a practice that continued until the 1970s.

Unexpected threat

Although Norman was a staunch anti-racism advocate, no one expected him to take a stand in Mexico. The Australian Olympic Committee had laid out just three rules for him to follow. The first was to repeat his qualification time before the Games.

“Rule number two: don’t finish last in any round,” Norman recalled.

“Third, and under no circumstances, don’t get beaten by a Pom (a British runner).”

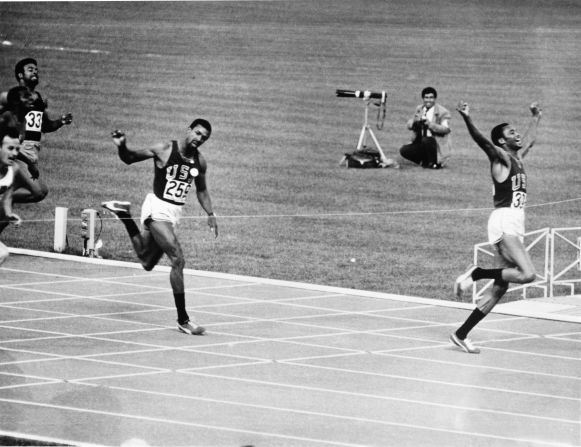

Norman had previously been ignored by the U.S. team, who had assumed they’d win a clean sweep of medals in the 200 meters, but he burst on to their radar when he broke the Olympic record in one of the early heats.

“When I first saw Peter, I said, ‘Who’s this little white guy?’ ” Carlos told CNN.

He would soon regret the oversight. When the 200 meters final arrived, all eyes were on the U.S. duo. Smith was expected to win easily (“You wouldn’t be able to catch him on a motorbike,” was Norman’s assessment) but the speculation centered on what political gesture the American athletes might make on the podium.

The starting pistol was fired and Smith powered to gold. But out of nowhere Norman stormed down the last 50 meters, taking the line before a shocked Carlos. Norman’s time of 20 seconds flat would have won gold four years later at the Munich Olympics and at the Sydney Games in 2000.

A fateful decision

Smith and Carlos had already decided to make a statement on the podium. They were to wear black gloves. But Carlos left his at the Olympic village. It was Norman who suggested they should wear one each on alternate hands. Yet Norman had no means of making a protest of his own. So he asked a member of the U.S. rowing team for his “Olympic Project for Human Rights” badge, so that he could show solidarity.

“He came up to me and said, ‘Have you got one of those buttons, mate,’ ” said U.S. rower Paul Hoffman. “If a white Australian is going to ask me for an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge, then by God he would have one. I only had one, which was mine, so I took it off and gave it to him.”

The three men walked towards their destiny. The medals were handed out before the three turned towards the flags and the start of the Star Spangled Banner.

“I couldn’t see what was happening,” Norman said of that moment.

“I had known they had gone through with their plans when a voice in the crowd sang the American anthem but then faded to nothing. The stadium went quiet.”

The fallout was immediate for Smith and Carlos, who were sent home in disgrace. Norman was never given the chance to go a step closer. He was never picked to run in the Olympics again.

“I would have dearly loved to go to Munich (but) I’d earned the frowning eyes of the powers that be in track and field,” he said in “Salute!”

“I’d qualified for the 200 meters 13 times and 100 meters five times (but) they’d rather leave me home than have me over there (in Munich).”

Shunned in his own country?

Norman retired from athletics immediately after hearing he’d been cut from the Munich team. He would never return to the track. Neither would his achievements count for much 28 years later when Sydney hosted the 2000 Olympics.

“At the Sydney Olympics he wasn’t invited in any capacity,” says Matthew Norman.

“There was no outcry. He was the greatest Olympic sprinter in our history.”

In his own country Peter Norman remained the forgotten man. As soon as the U.S. delegation discovered that Norman wasn’t going to attend, the United States Olympic Committee arranged to fly him to Sydney to be part of their delegation. He was invited to the birthday party of 200 and 400-meter runner Michael Johnson, where he was to be the guest of honor. Johnson took his hand, hugged him and declared that Norman was one of his biggest heroes.

“Peter was not sanctioned … we are not sure why he missed selection in 1972 but it had nothing to do with what happened in Mexico,” the Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) told CNN when asked about Norman’s exclusion from the team that traveled to Munich.

“Peter was not excluded from any Sydney 2000 celebrations.”

The AOC points out that Australia’s greatest ever sprinter had been given several crucial roles in the festivities.

“He represented the AOC at several team selection announcements,” it said, “including the announcement of the table tennis team in his home town of Melbourne prior to the Sydney Games.”

Remembering Peter Norman

When “Salute!” was released in Australia in 2008 it caused a sensation, breaking box office records. In a country known for its reverence of sporting legends, many were hearing Norman’s story for the first time. But he would never see the film that would put his achievements back into the public consciousness.

Peter Norman died of a heart attack on October 9, 2006.

At the funeral both Smith and Carlos gave the eulogy, where they announced that the U.S. Track and Field association had declared the day of his death to be “Peter Norman Day” – the first time in the organization’s history that such an honor had been bestowed on a foreign athlete.

Both men helped carry his coffin before it was lowered into the ground. For them, Norman was a hero – “A lone soldier,” according to Carlos – for his small but determined stand against racism.

“He paid the price. This was Peter Norman’s stand for human rights, not Peter Norman helping Tommie Smith and John Carlos out,” Smith told CNN. The three had remained friends ever since their chance meeting on that podium in Mexico City 44 years ago.

“He just happened to be a white guy, an Australian white guy, between two black guys in the victory stand believing in the same thing.”

A proud legacy

Arguably the biggest price Norman paid was the fact that his run in the 200 meters final had been obscured by the Black Power salute. It remains to this day one of the finest, and least expected, individual performances by a sprinter at the modern Olympics.

By the end of the final, Norman had shaved half a second off his best time. His full potential was never realized yet, even after the ignominy of his return, Norman bore no grudges.

“It has been said that sharing my silver medal with that incident on the victory dais detracted from my performance,” Norman explains poignantly at end of “Salute!”

“On the contrary. I have to confess, I was rather proud to be part of it.”